IMPRESSSIONS: The Batsheva Ensemble performs “Kamuyot” at 92nd Street Y

Choreography: Ohad Naharin

Dancers: Zoe Bayliss Nagar, Zachary Burrows, Jesse Callaert, DanDan Cohen, Victor Duval, Eddieomar Gonzales-Castillo, Shira Kestenboum, Larissa Leung, Ori Manor, Maya Marom, Celia Merai, Chase Peterson, Leann Reizer, Kelis Robinson, Noga Sneh

Costume Design: Sharon Eyal, Alla Eisenberg

Sound Design: Dudi Bell

Batsheva Ensemble Manager: Idan Porges

Ohad Naharin's Kamuyot, a fan favorite since its premiere in 2003, begins before it begins.

Seated around the perimeter of 92Y's spacious Buttenweiser Hall, audience members meet and converse, our voices creating a pleasant hum. The Batsheva Dance Ensemble dancers casually enter and sit amongst us, becoming part of the buzzing conversation. Only when they rise together and walk to the center of the room do we realize Kamuyot began ten minutes ago, and we are all part of it.

At the heart of the show is a proposal — an appeal to joy, an invitation to connect and be together in this time and place, and to dance. Eschewing conventional theater trappings — a proscenium set-up, performance lighting, and distance between stage and seats — Kamuyot breaks down the barriers between performers and audience members in fifty minutes of playful, high voltage, impeccably nuanced, and riotously free dance.

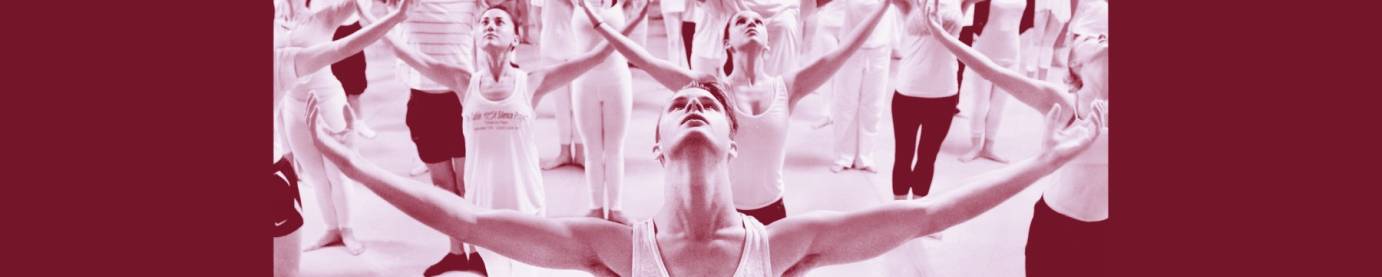

Clad in assorted plaid pants and kilts layered with colorful ripped and fishnet tights, the dancers repeatedly shift directions, offering each audience member a personal vantage point. One by one, each of the piece’s fifteen performers are highlighted in physically demanding, highly technical, oozing yet sculpturally specific solos before blending back into the group, which moves like a single entity. One soloist propels through space using only the momentum of his own slaps against his body. Another duet sees a woman sensuously circling her hips while a man kisses her feet. Kamuyot’s movement vignettes range from wacky to soulful, each one imbued with the intricacy and personality audiences have come to expect from Naharin’s Gaga movement language, which emphasizes each dancers’ somatic experiences over a codified technique. It is a delight to see each one of these incredibly proficient movers stand out as unique individuals in such a large group. Joy is Kamyout’s most unmistakable theme, driven home by the absence of traditional stage lighting, which allows both the performers’ movements and the spectators’ reactions — enchantment, discomfort, and excitement — to be seen equally.

But Kamyout is not only about spectating; it is about participating, and audiences are able to choose their level of interaction with the work. Out of all artistic mediums, I’ve found that dance is supremely suited to foster empathy and connection. There is nothing like moving with another person beyond the confines of words to create a bond that, no matter how brief, is deeply felt. In Kamyout, unison phrases lead the performers to different seats next to different people, and from time to time they invite their neighbors to the stage for short moments of guided movement, silently leading their partners through a series of slow, unison shapes. While much of the choreography is extremely complex and demanding, these mirror moments are simple and accessible. Yes, the dancers are impeccably trained professionals, but in these moments Naharin reminds us that virtuosity is not all that dance has to offer, and invites us to consider movement as a spectrum on which everyone can participate.

In perhaps the most heartwarming portion of the evening, the ensemble walks slowly around the perimeter of the space making eye contact with everyone they pass before stopping to hold the hand of whoever is in front of them. Each hand holding lasts considerably longer than a normal handshake and creates a profound sense of intimacy and acknowledgment. It is beautiful.

Throughout the work the sound score is ever-shifting. Like the dancing that fluctuates from percussive isolations to suspended flow, sound designer Dudi Bell samples everything from Beethoven to Lou Reed and Steve Reich, creating an auditory smorgasbord that sometimes feels like a video game and others a scene from an Austin Powers movie. The transitions between the music segments seem purposefully jarring, pulling attention toward the flavor of each movement vignette, and intensifying ecstasy.

The finale is a dance party with very little pressure to participate; you can choose to join or exit. Very few people leave. Gradually, you realize that the performers have unobtrusively left the communal space they initiated, and you find yourself in an undulating crowd, smiling and sharing a singular moment in time with strangers. Sharing the joy of dance. For this, Batsheva Ensemble, we thank you.