IMPRESSIONS: Ballez in “Travesty Doll Play Ballez (after Coppélia)” at Chelsea Factory

Choreography: Katy Pyle

Performers: Julia Assue, cove barton, Jay Beardsley, MJ Markovitz, Katy Pyle, Arzu Salman

Original Score: Lavinia Eloise Bruce & Scott Killian

Additional Music: ‘Mazurka’ and ‘Valse’ from Léo Delibes 1870 “Coppélia,” performed by Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, conductor Andrew Mogrelia

Lighting Design: Amanda K. Ringger

Costumes: Karen Boyer

Production Stage Manager: Mika Kauffman

Since 2011, choreographer and performer Katy Pyle has found their place queering the ballet canon through Ballez, a dance company centered on “a radical reformation of ballet culture, aesthetics, and representation.” Ballez brings queer, trans, and gender nonconforming dancers together in community to craft vital pathways toward self-discovery and self-expression through ballet training and performance. This is a daring move within the highly-gendered world of classical ballet, within which a stark gender binary persists in molding bodies and minds to rigid technical standards and artistic expectations. Pyle confronts these issues head on by offering open classes and reshaping ballet’s masterpieces through a queer lens, from “Sleeping Beauty,” “The Firebird,” and “Giselle,” to their most recent foray: “Coppélia.” The Ballez renditions veer away from one-for-one retellings of old tales, functioning rather as points of departure for case studies within classical narratives or imaginative leaps beyond these frames.

“Travesty Doll Play Ballez (after Coppélia)” continues this mission, using abstracted character portraits to shape a dance that is as thoroughly queer as it is intimate, exhilarating, and confusing. This confusion is intentional — backed by pervasive and often playful ambiguities — and lends substance to the experience of gender’s capacity to confine, perform, and liberate. The six Ballez performers (who are transgender, gender nonconforming, and/or genderqueer) each bring a self-possessed sense of expression that is at once distinctive, slippery, and authentically radiant. Their individual and collective empowerment elicits empathy and wonder while shattering the performative fourth wall; their passion and commitment to themselves, each other, and the work remains viscerally evident as they shapeshift before us. Wherever they may fall short in technical rigor and finesse they more than recover in the stories their bodies tell through these very (perfect) imperfections.

Pyle’s research and creation process for the work spans historical, personal, and interpersonal spheres, as outlined in a program excerpt from Coco Romack’s forthcoming Sense of Shifting: Queer Artists Reshaping Dance. Through Ballez Pyle excavates and reclaims the queer history of “Coppélia,” which remains a staple of ballet’s classical repertory with its charming story of village-boy-meets-village-girl amid the machinations of a doll maker and his lifelike girl doll. Its 1870 premiere at the Paris Opera featured danseuse étoile Eugénie Fiocre dancing the lead role of Franz en travesti — at the time most male roles were danced by women — leaving a queer imprint on canonical steps that continue to be performed today. Personal and interpersonal questions arise as Pyle and the Ballez dancers take on the work, as documented in "Travesty," an episode of the All Arts Series “Past Present Future". The short film — and certainly the dance itself — demonstrates how each dancer brings with them a wealth of individual and intersecting experiences of gendered oppression, violence, affirmation, and play.

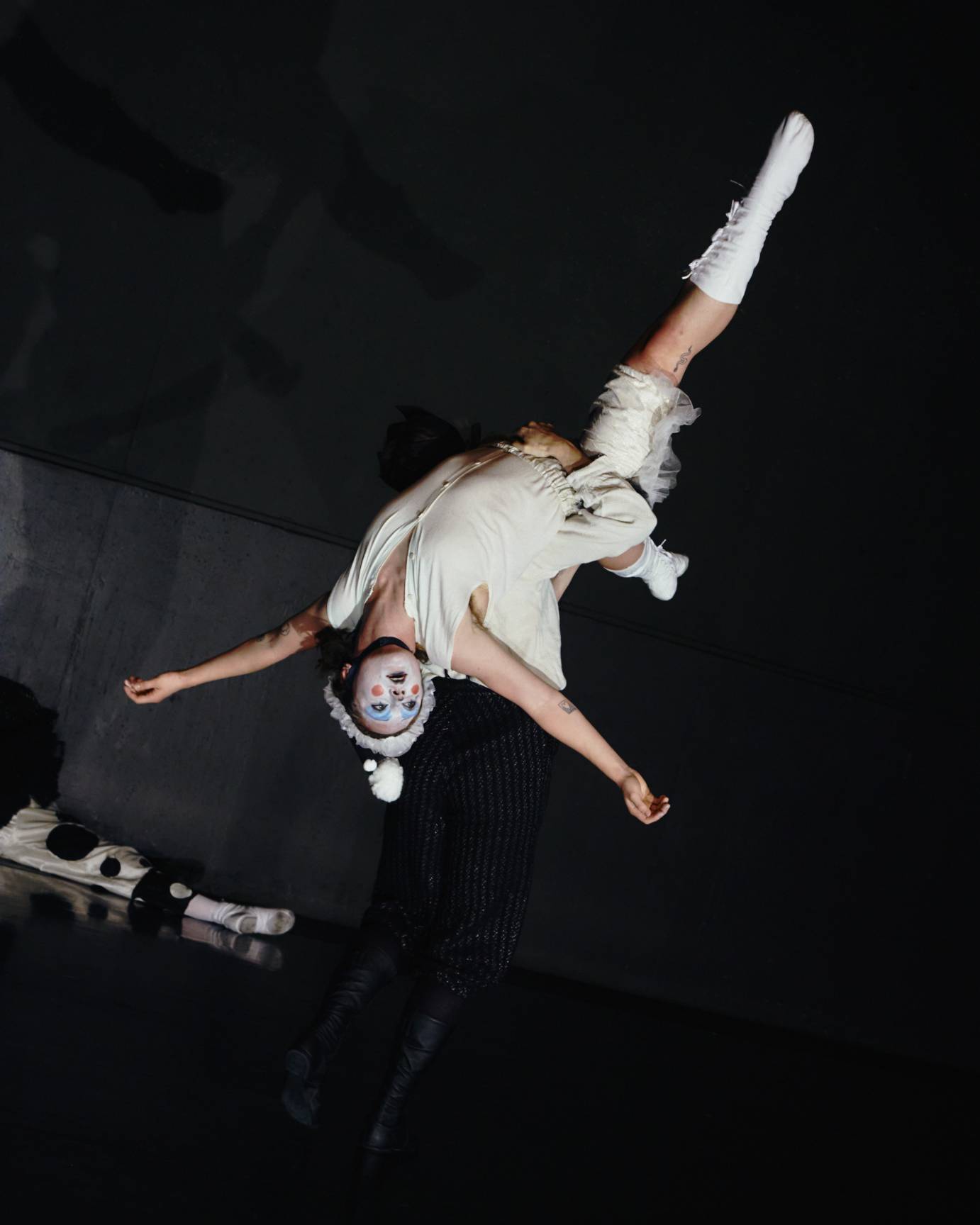

“Travesty Doll Play Ballez” thrives on a multidimensional attunement to the power of transformation. While eschewing staged sets and linear narrative devices in favor of an open, abstract expressive arena, its sense of place and purpose remains grounded in a robust theatricality. Musically, the work fractures Léo Delibes original score through a mosaic of traditional orchestral recordings and original departures and renditions composed and performed by Lavinia Eloise Bruce and Scott Killian. Passages of piano and percussion shape interludes and character arcs with glowing tenderness while booming bass and synth compositions veer toward the depths of trauma and angst or soar into the cathartic delights of high camp. Amanda K. Ringger’s sensitive lighting guides the artists’ journeys from clinical brightness through murky darkness and dissociative madness to emerge into the reconciling warmth of a humane amber glow. The strong silhouettes of Karen Boyer’s bold black-and-white costumes vocalize the struggle against the binary for the Doll Maker and each of their doll archetypes: Soldier, Fairy, Clown, Ballerina, and Sailor. The dolls engage first in the rigid gender performances determined by their garb; gender anarchy takes over as the dolls come to life, stripping off and exchanging a flurry of costume pieces over neutral undergarments.

Pyle’s choreography, grounded in classical ballet with explicit nods to “Coppélia,” makes the most of the small and scrappy cast with simple phrasing and clear structures through which to deploy devices of quotation, mirroring, and distortion. As the Doll Maker, Pyle sets the tone with an opening solo that recurs in increasingly contorted iterations as their grip on the Dolls tightens and loosens. The Doll Maker acts as creator, enforcer, and abuser, a role that Pyle inhabits as a frankly chilling portrayal of gendered hegemony, domination, and eventual redemption. Group dances for the Dolls speak of mechanized conformity through rigid two-dimensional unison sequences of technical maneuvers delivered with deadpan precision. A brash mazurka presents a gendered farce of shifting solos and duets that highlight the binaries inscribed in ballet technique.

In the absence of their Maker, the dolls break free in explosions of virtuosity and freewheeling abandon, devouring space with a litany of leaps and turns. When the Maker bursts in on the rebellion, they proceed to punish the Dolls, gripping and dragging their bodies to put them back in their places. An extended duet for Pyle and the Clown (MJ Markovitz) vividly portrays the horror and pain of physical and psychological manipulation as the Clown forcibly retreats into their shell, a dim shadow of themself. Healing is not out of reach, however, as the Dolls awaken once again — makeup smeared off, costumes stripped down — and unfurl into lush, three-dimensional solos and meditative duets. They slow down to share weight in expansive counterbalances and lifts, sustain direct eye contact, and move into tender embraces. We can almost feel their breathing and heartbeats sync as they emerge, fully human, to see us too.