Impressions of: American Ballet Theatre in "The Green Table"

October 21 to November 1, at the David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, New York

Book and Choreography by Kurt Jooss

Music by F.A. Cohen

Costumes by Hein Heckroth

Masks and Lighting Design by Hermann Markard

Staging by Jeanette Vondersaar

Repetiteur: Claudio Schellino

Lighting directed by Brad Fields

American Ballet Theatre first performed Kurt Jooss’s anti-war masterpiece The Green Table in 2005, in the aftermath of the “shock and awe” campaign that launched the Iraq War. Loudspeakers spewing propaganda had shouted down dissent at the start of the war, but as they grew quiet artists began to re-assert their moral authority and raised their voices to condemn American militarism. In addition to the revival of The Green Table, 2005 saw the premiere of Bill T. Jones’ Blind Date, a scathing piece questioning the value of patriotism; and Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker performed her solo Once, set to songs of protest by Joan Baez. The following year, Paul Taylor would join the anti-war chorus with his Banquet of Vultures. Ronald K. Brown had made his feelings known in Come Ye (“Ye who would have peace”) as early as 2002.

No one can say our artists haven’t warned us. Jooss made his stylized dance of death in 1932, following the slaughter of World War I but well before the tragedies of World War II unfolded. The Joffrey Ballet revived The Green Table in the midst of the Vietnam War. Yet here we are—still. As of this writing, American troops remain on active duty in Afghanistan; while in Syria bombs are flying and desperate refugees take to the sea in boats. The artists won’t give up, though. They keep reminding us of war’s folly in the hope that someday reason will prevail.

This autumn, as part of its 75th-anniversary season, ABT brought back The Green Table giving audiences another chance to view this haunting work in which Jooss strips away all pretense of “realpolitik” or martial glory.

The ballet begins in darkness, with a crash; and then Frederick Cohen’s skeletal piano music takes up a see-saw rhythm that recalls the march of soldiers or the tolling of a bell. This ominous melody gives way to a tango, as the lights come up on a scene far distant from the battlefield. Here dignitaries wearing silk jackets and white gloves (the “Gentlemen in Black”) perch along the edges of a green baize tabletop where, if negotiations were not taking place, the same idlers might be found betting on cards. Instead of baccarat or poker, however, they have another game. One points his finger and another slaps the table in remonstrance. When a “speaker” places his foot on the table and makes flourishing gestures, a faction applauds his acrobatic oratory. Stepping away from the table, these popinjays fence back-and-forth, and then stop to bow to one another with unctuous politesse (“After you, dear colleague!”). Their hollow-eyed masks seem cheery, yet they are also scabrous and inhuman. Finally the Gentlemen in Black line up to face us. It seems they have reached an agreement. Crossing one foot over the other casually, they fire pistols into the air.

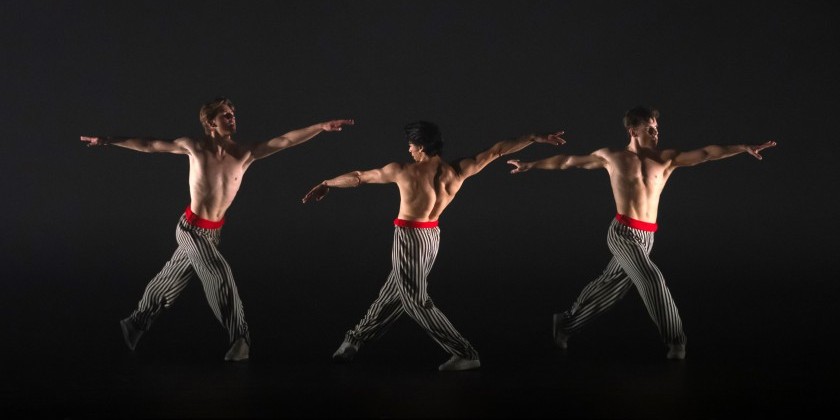

Now the devil has been unleashed, and soon we see him—Death, himself—in the ghoulish uniform designed by Hein Heckroth, with straps around his chest like ribs and a leather apron like a pelvis, a dark-crested helmet shadowing his gaunt features. Jooss gives this specter a distinctive, angular stance with one leg stretching sideways. Hunched and stamping his foot he sweeps all before him with a scything gesture. He rears up to deliver a smashing blow, and retreats with a devious twist of his knee.

The Standard Bearer waves his flag, but it is Death, flexing his bicep, who summons the recruits in “The Farewells.” The first soldier comes tramping in and swinging his elbows with a step and gesture that are too large for him, like a child trying on a man’s clothes. The next soldier has his sweetheart clinging to him. She begs him not to go, resting her head tenderly against his hand, and she blocks his path with her face raised for a kiss---all to no avail. The third soldier arrives with another woman and his old mother in tow. Who will sustain them, when he’s gone? Then we meet the Profiteer, his bowler hat tipped open to receive favors. He salutes Death cheekily. It seems they know each other! Hungrily the Profiteer sizes up the Young Girl. This hyena can scarcely wait to claim her, now she’s all alone; and in contrast to the freshness she displayed a moment ago, now she crouches shriveled with fear.

Hardly anything has happened, and yet it’s clear where these events will lead. Jooss sketches his characters in the instant when their world comes apart; and our imaginations can do the rest. We already know this story from generations of sad experience. Yet in their stylized dignity these archetypal figures have an extraordinary power to move us. As in a 19th-century melodrama, “The Green Table” portrays despotism and its helpless victims. It draws attention to injustice, and reveals the suffering war inflicts to be a timeless moral truth.

Significantly, in “The Battle” Jooss does not introduce rival armies with contrasting insignia. The handful of soldiers tugging back-and-forth and falling limp at Death’s command are all the same, all dupes. Until the Standard Bearer’s flag grows stained, it remains blank. Feel free to paint any nation’s colors there, or write any excuse you want---“lebensraum,” the spread of Communism or weapons of mass destruction. As soon as the soldiers are dead, the Profiteer twirls in inspecting the bodies. What’s this? A wedding ring, perhaps? He’ll take it!

In “The Refugees” a small clutch of women stands huddled near the wings. As if she feels a premonition, the Old Mother separates herself from this group, feeling her way in the darkness and pressing her hands frailly against the unknown. When Death awakes in the far corner, the refugees flee. But for the aged flight is impossible. At first the Old Mother shrinks, but then she takes Death’s hand and we see how gallant he can be, adopting a ballroom pose with jaunty hand-on-hip before he gathers her up. In real life, of course, Death reserves no tenderness for the old; and it’s odd to consider that Jooss has slipped in a euphemism.

The point of The Green Table is not to repel us, however, or, heaven forbid, incite us to further violence with graphic images of war’s effects (like the televised footage showing victims of a gas attack in Syria). No, Jooss’s purpose is to recall the sentiments that govern our conduct under normal circumstances, until a freakish outbreak of psychosis—motived by greed, or fear or the impulse to dominate—dictates we abandon all scruples and everyday notions of decency. The Green Table seeks to re-set our moral functions, with good will and kindness as the default. From this perspective, there is no such thing as “collateral” damage.

In “The Partisan,” we see another doomed attempt at heroism. Though her gestures are bold, the character who gives this section its title also skulks, peering out from behind her arm as if in a place of concealment. Yet her case is as hopeless as the others. When she emerges to strike a rear-guard soldier with her scarf, she is instantly caught. Then Jooss introduces some filmic techniques, as Death leads her in reverse to the firing squad. Her life rewinds and her passion drains away in slow motion, before she succumbs to Death bowing at his feet.

In “The Brothel,” the Profiteer at last has his way with the Young Girl. He wasn’t planning to keep her for himself, but sets her whirling in the arms of a succession of anonymous “dates.” For a moment, it appears as if she might have a chance at redemption. As this dancehall orgy winds down, she stretches her arms toward her beloved, who approaches from a distance. Yet at the crucial moment they miss each other, and he passes by. Death claims the Young Girl instead, and she seems chained to him as she runs wildly in a circle. The final image of their duet is unforgettable. Crouching over the Young Girl’s prone body, Death sniffs at her; and he raises his head to stare at us like a predator interrupted while devouring a carcass.

The war depicted in The Green Table is never won. In “The Aftermath” the Standard Bearer finally succumbs, revealing himself to be as helpless as the others. Death strings all his victims together, and they totter around him mechanically before they exit parading out at his command. But what of the Profiteer? A wind appears to blow as this miscreant seeks to evade the final round-up, but even though the puny fellow is no match for Death he manages to escape, holding on to his bowler hat as he tumbles into the wings. There will be no end to his mischief.

Nor does Jooss see an end to the misery he recounts. His ballet, like war itself, is cyclical, ending as it began with the Gentlemen in Black leering at us as they rehearse their ridiculous postures around the green baize table. The only victory belongs to ABT, for preserving this courageous and essential work in its repertoire.

Several wonderful dancers stepped into these time-honored roles. As Death, Marcelo Gomes assumes the part that Jooss created for himself, making his tall frame hulk and his movements ooze like blood until, with a sudden sharpness, his body goes rigid. Even in his fright makeup, Gomes remains seductive. His alternate, Roman Zhurbin, brings weight to the role, at times seeming pained as if the grimness of Death’s task haunted him. Blaine Hoven’s chiseled figure and dismayed but resolute expression are perfect for The Standard Bearer. As the Young Girl, Sarah Lane gives a performance of startling extremes, and her impact is tremendous. Luciana Paris makes a delicate and soulful Old Mother; and Herman Cornejo translates his physical authority and slickness into a sleazy and demanding caricature as the Profiteer. The alternate Profiteer, Daniil Simkin, seems miscast; it’s hard for this ingénue to appear depraved.

American Ballet Theatre’s fall season included many other star turns, of course. On opening night, Veronika Part gave a luminous account of Monotones II, offering a gorgeous line, airy lightness and hints of voluptuousness. Twyla Tharp’s Brahms-Haydn Variations includes a series of cameos amid its magnificent, contrapuntal machinery; and new interpreters lend these portraits different shadings. The duet that Tharp choreographed for Julie Kent and Angel Corella still has the feeling of a pastoral romp, but Cornejo and Maria Kochetkova add a sexual frisson emphasizing her delicacy and his protective muscle. They’re not just brother-and-sister. In the mysterious, searching number that Tharp created for Irina Dvorovenko and Maxim Beloserkovsky, Christine Shevchenko and Joseph Gorak exude a dark, romantic vapor that makes them feverish. Paul Taylor’s Company B comes packed with opportunities, and dancers like Shevchenko (“There Will Never Be Another You”), Gorak (“BoogieWoogie Bugle Boy”) and Gabe Stone Shayer (“Tico -Tico”) made the most of them. It would have been a shame to miss Cassandra Trenary as the enraptured debutante in Le Spectre de la Rose.

All these ballets are wonderful; but none of them, alas, has the relevance of The Green Table, which still illustrates the headlines and exposes today’s lies.

Share Your Audience Review. Your Words Are Valuable to Dance.

Are you going to see this show, or have you seen it? Share "your" review here on The Dance Enthusiast. Your words are valuable. They help artists, educate audiences, and support the dance field in general. There is no need to be a professional critic. Just click through to our Audience Review Section and you will have the option to write free-form, or answer our helpful Enthusiast Review Questionnaire, or if you feel creative, even write a haiku review. So join the conversation.