IMPRESSIONS: Akram Khan’s Wondrous "Jungle Book reimagined" at Lincoln Center

The Kipling Classic Set Amid a Devastating Climate Crisis

Director/Choreographer: Akram Khan

Creative Associate/Coach: Mavin Khoo

Writer: Tariq Jordan

Dramaturgical Advisor: Sharon Clark

Composer: Jocelyn Pook

Sound Designer: Gareth Fry

Lighting Designer: Michael Hulls

Visual Stage Designer: Miriam Buether

Art Director/Director of Animation: Adam Smith (Yeastculture)

Producer/Director of Video Design: Nick Hillel (Yeastculture)

Rotoscope Artists/Animators: Naaman Azhari, Natasza Cetner, Edson R. Bazzarin

Rehearsal Director: Nicky Henshall

Dancers: Maya Balam Meyong, Tom Davis-Dunn, Harry Theadora Foster, Filippo Franzese, Bianca Mikahil, Max Revell, Matthew Sandiford, Pui Yung Shum, Elpida Skourou, Holly Vallis, Jan Mikaela Villanueva, Luke Watson

Voice Actors: Tian-Lan Chaudhry, Joy Elias-Rilwan, Pushkala Gopal, Dana Haqjoo, Nicky Henshall, Su-Man Hsu, Kathryn Hunter, Emmanuel Imani, Divya Kasturi, Jeffery Kissoon, Mavin Khoo, Yasmin Paige, Max Revell, Christopher Simpson, Pui Yung Shum, Holly Vallis, Jan Mikaela Villanueva, Luke Watson, 3rd Year Students of Rambert School

Assistant Animators: Nisha Alberti, Geo Barnett, Miguel Mealla Black, Michelle Cramer, Jack Hale, Zuzanna Odolczyk, Sofja Umarik

Rose Theater at Lincoln Center, November 16-18, 2023.

What makes Jungle Book reimagined such a wondrous two-hour, dance-theatre adventure is how magically it amalgamates pairs of differing expressive modalities to concoct its mysteriously unified story-telling components. Presented at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theatre for a 3-day run in November, the 2022 work is directed and choreographed by Akram Khan. Long celebrated for his innovative fusion of Indian and contemporary dance, the British Bangladeshi choreographer here shows he is also an imaginative helmsman of multi-disciplinary theatre. To tell its fantastical tale — based on Rudyard Kipling’s 1894 classic The Jungle Book and Disney’s eponymous 1967 animated film — Khan’s production renders dramatic characters, settings, and events by brilliantly coupling onstage and onscreen images, live action and animation, real dancers and recorded voice-overs, choreography and text, and sounds and music.

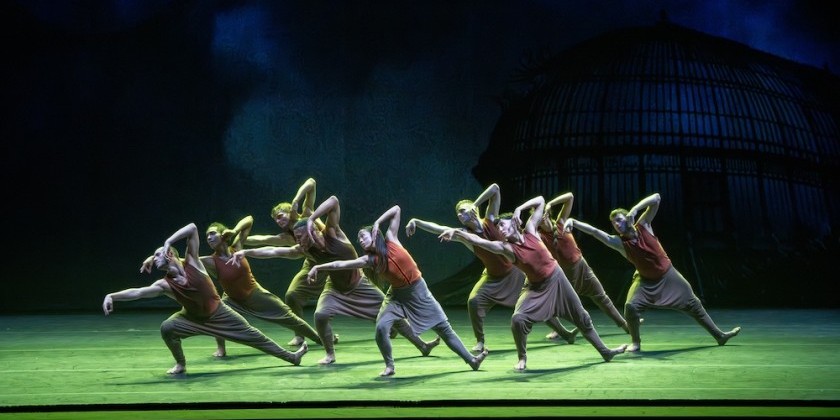

Akram Khan Company's Luke Watson, Maya Balam Meyong, Matthew Sandiford, Harry Foster, Pui Yung Shum, Max Revell, Holly Vallis, Bianca Mikahil, Filippo Franzese in Jungle Book reimagined. Photo: Richard Termine

While the story is enacted onstage via the movements of the Akram Khan Company’s 12 agile dancers, their live motions are often performed in conjunction with video animation (by Yeastculture’s Adam Smith and Nick Hillel). And though, externally, one can clearly distinguish between what’s physical and what’s projected, in the “mind’s eye” the two merge, and the dramatic content of what’s being portrayed supersedes our awareness of any distinction between dancers and drawings. Visually streamlined, the show’s affecting animation is not of the high-tech super-realism ilk, but rather limned to look pencil-drawn, making its powerful expressivity that much more surprising. A screen full of slashes (albeit augmented by Michael Hulls’s shadowy lighting) conjures a truly frightening rainstorm at the top of the show, while later an animated flock joins the gatherers at a fellow bird’s funeral, furiously flapping their wings in an outpouring of grief that proves tear-jerking.

Similarly, it’s tight pairings of onstage dancers’ body movements and recorded voice-overs of spoken dialogue (written by Tariq Jordan) that establish the show’s main characters — most of which are animals. Each character’s “existence” amalgamates only within the viewer’s imagination. And so convincing is the kinship between the dancing and the text that it’s easy to forget that the live performers are not actually talking. The show’s choreography is set, quite strictly, to the dialogue, not to musical counts or phrasings (with the exception of a few pure-dance ensemble sequences). Much of the choreography uses the floor as its canvas and derives inspiration from animal movements, with enough hints of hip-hop, Indian dance, and contemporary technique to keep it aesthetically interesting. Also striking, is how persuasively the characters are portrayed without the assistance of facial expressions or costuming. The lighting is so dim that one can’t clearly read the dancer’s facial features, and the entire cast is costumed alike in generic dancewear.

Underscoring the drama throughout is Jocelyn Pook’s smart soundscape, which keenly mixes music and nature sounds to evoke the story’s environmental setting and this production’s added focus on climate change. Plot-wise, Khan’s reimagining strays little from the original episodic tale of Mowgli, a lost child raised by wolves. Though the villainous tiger is gone, Mowgli still encounters the comic bear, the nurturing panther, the hypnotic python, the ridiculous monkeys, and wise communities of elephants and birds. Yet while retaining the theme of respect for non-human animals, Khan made some astute updates to resonate with contemporary sensibilities. Mowgli is now a girl, and the plot is initiated by a devastating global flood from which Mowgli is rescued by the animals, all of whom now have back-stories explaining how mankind’s cruelty caused their problematic personality traits. The monkeys were abused in lab experiments and have adopted human values and behaviors, while the bear was forced to dance as a circus entertainer, and the python was locked up in a glass case in a zoo. Thematically, compared to Kipling’s, Khan’s Jungle Book is less concerned with humans’ relationships with one another and more critical of man’s treatment of the natural world. Khan uses the monkeys to serve up a harsh critique of mankind’s self-importance and the out-sized value we place on our freedoms. Inconsistently, however, he has Mowgli remember her sage mother telling her (via flashbacks) that she possesses within herself everything she needs to succeed. Hmmm…isn’t that the epitome of self-importance?

Because there is no role-casting delineated in the program’s alphabetical list of dancers, I’m not sure whom to credit, but I would love to give shout-outs to the two performers who danced the parts of the bear and the panther. The bear, for a superb bit of mime work, showing his struggle to break down the invisible glass wall imagined by the psychologically still-imprisoned, PTSD-suffering python. And the panther, for slinky walking on all fours that emulates the perfectly cat-like locomotion of the Disney animation – the key, I think, is in the loose, asymmetrical responsiveness of the shoulder joints.

While the enthralling production will appeal to climate change-conscious teens and adults, I don’t suggest it for very young children. Though its “be kind to animals” message may be relevant and important for them, not only is there no happy ending and little comedy, but the production takes a dark turn in the second act, growing violent and disturbing. I found the dance by a lone monkey, recalling the electric shocks administered to him by scientists, virtually unwatchable. Ultimately, the show leaves audiences with the idea that a youngster who now understands everything Mowgli has come to learn is burdened with the task of teaching the rest of mankind what they must do to save our planet. A big responsibility to place on little shoulders.