THE DANCE ENTHUSIAST ASKS: Janet Wong On Dance Theater and Working with Bill T. Jones

Janet Wong was born in Hong Kong and trained in Hong Kong and London. Upon graduation, she joined the Berlin Ballet where she first met Bill T. Jones when he was invited to choreograph on the company. In 1993, she moved to New York to pursue other interests. Ms. Wong became rehearsal director of the Company in 1996, associate artistic director in August 2006, and associate artistic director of New York Live Arts in 2016.

Anabella Lenzu, Moving Visions Editor for The Dance Enthusiast: Janet, I am so interested in how your career led you from Hong Kong, to London, to Germany, to working with Bill T. Jones in New York City. Can you tell me a bit about your journey?

Janet Wong: I was born in Hong Kong. When I was seven, we moved to Singapore. I started ballet at the time. I was around 10-years -old when we moved back to Hong Kong. I had to put dance on pause to acclimate to the school system there. When I was ready, I told my mom I wanted to study ballet again. At 16, I got a scholarship to to the Royal Ballet School in London, and was there for two years. In the second year, I traveled around Europe, and worked with the Deutsche Oper Berlin. I was there for eight years.

Sometime in my fifth year, Bill T. Jones was invited to choreograph on the company. When he came, my mind just blew open. It was the way he played with ideas. Working on that project lit my soul aflame. My mind was opened and, I thought, “I need to work with a living choreographer.” (I worked with so many dead choreographers.)

I quit my job to come to New York. I also wanted to go back to school, and got into Fordham University, which I also didn't finish because I started working with Bill. I danced with the company for a season at the Joyce Theater. After a year, Bill called me and asked if I’d be his rehearsal director. We decided to try it for six months and six months later, we agreed that it was working well.

How did you come to learn about the phenomenon of Dance Theater?

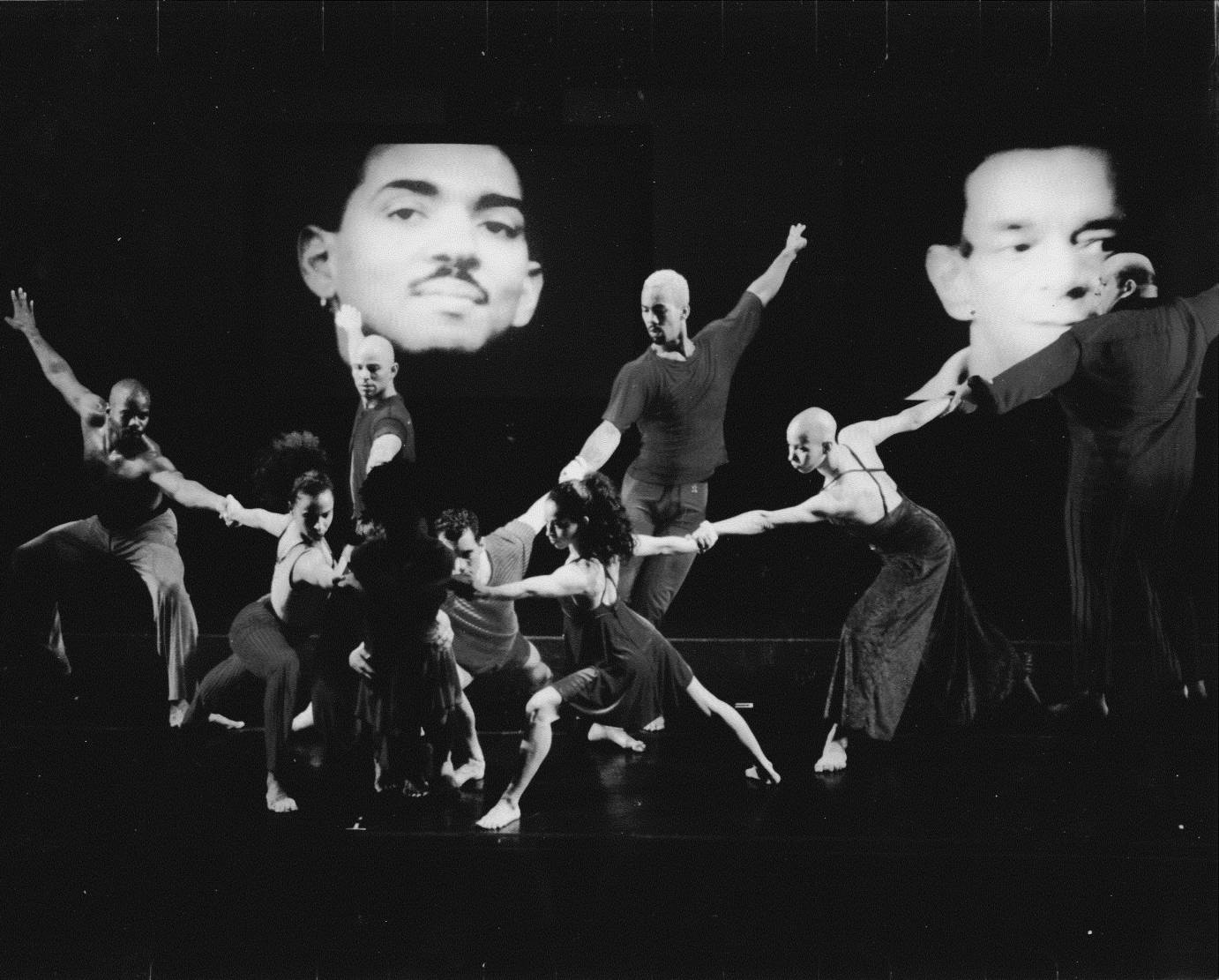

I’m not a historian, but thinking back towards the beginning of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company, the company was founded on big Dance Theater work — a form of American Dance Theater. It is not Pina Bausch, but it lives very close to that, at least for us. It lives very closely to and parallels our social-political currents. It is determinedly contemporary.

From the very beginning, I've been influenced by Bill and Arnie, although I've never met Arnie. I think their interest in avant-garde cinema and visual arts set them apart. They’re not solely focused on movement.

Bill was never part of the Alvin Ailey crowd. Making work with a group of people with diverse interests resulted in those duets that I love. So in that sense what they were doing was always political. Their bodies were part of politics.

How does the Dance Theater of Bill T. Jones compare to that of European Tanz Theater?

For me Dance Theater was heavily influenced by Pina Bausch, and before that, by Kurt Jooss and his group. But Pina Bausch, maybe there are pieces where with no dance in them, just smoky theater with long dresses, hair, and more hair. In a sense, it speaks very much to avant-garde theater where the narrative is not important. You can have episodes that may or may not add up to a whole.

Our dance theater is very body-based. The body is important, not more or less important, but significant, especially in a work that has language. I would say that one of our strengths, and maybe our weakness, is that we juxtapose many things. There's a collage of elements, and when it works well, the piece is larger than the sum of its parts. It leaves reverberations in the space and creates its own meaning which is outside of our control. This is what I like for the work to do.

So, putting very abstract formal movement together with a potent text, what does that do? Does it equalize it? Do movement and text affect each other?

Let’s talk a bit about your creative process working with Bill T. Jones. How do you begin to work on a new piece?

Different pieces start differently. Sometimes it starts with a title. Bill loves to say, “Naming things is only the intention to make things.” It's a Frank O'Hara quote. So, having a title frames the way you think. Sometimes it starts with text or a book. Other times, it begins with a big abstract idea. In the past, we've started with music, like commissioning chamber music works for a dance piece. Sometimes, it's like, 'Okay, we need to do a dance piece that uses classical music to fit into this classical music program,' and then we'll choose a piece of music. But most of the time it starts with an idea.

What is your relationship to Bill as he creates? Do you provide the big picture while he delves into the microcosm of the work or…?

The line is very fluid. We could be doing choreography, and then the next hour, he and I might be in his office text editing. We have also worked with the dramaturg. It's hard to say who did what… I'm very involved in dramaturgy; I love playing with the syntax, context, and content of the piece — what is said, heard, and seen. I love those things. When I do the visual design, projection design, I come in last because I can't share my work until I'm in the theater. During that time, I'm part of the rehearsal, part of the creative process.

Sometimes we fight, of course. We work very closely together, and there's trust — almost an unspoken understanding after 27 years. The collaboration goes on, even remotely. The idea behind the work, the thinking and feeling, is always important to Bill. What is in his mind and heart matters. Maybe there's always anger, but there's also hopefulness. Otherwise, why make art in the world's current state? It's so devastating.

Can we talk a little bit more more about the balance in your artistic relationship?

He's bringing the West, bringing the African-American. Sometimes he brings the East, and I bring the West. It's really funny. First of all, our energies balance. I am the calm one. My ego is much less developed; it's not important to me. The work is important, and the well-being of people is crucial because it's not worth it if you cannot embody your values both in your work and in the way you behave outside in the world.

Bill and I work well together; we fight, but we know deep down that we care for each other. It's more challenging in the context of New York Live Arts because we're also the artistic leadership of New York Live Arts.

Everything requires time, energy, and effort. How do you not do things half-heartedly? You have to do them well. And then you have to fail, learn, and make room for others to fail and learn. That's a hard part, especially for me. I'm judgmental at times. Learning your flaws is essential, but I don't think there's a magic solution. There is understanding. Maybe there's magic. Bill likes to say that we're married, and in the artistic way, we are married. I very much cherish that relationship and the way I am allowed to grow in this partnership, given opportunities that I wouldn't have had elsewhere.

Also, I think women should run the world!