IMPRESSIONS: Dimitris Papaioannou’s “The Great Tamer” at BAM Howard Gilman Opera House

November 15, 2019

Conception and direction: Dimitris Papaioannou

Performance: Pavlina Andriopoulou, Costas Chrysafidis, Ektoras Liatsos, Ioannis Michos, Evangelia Randou, Kalliopi Simou, Drossos Skotis, Christos Strinopoulos, Yorgos Tsiantoulas, and Alex Vangelis.

Set design in collaboration with Tina Tzoka // Costume design in collaboration with Aggelos Mendis

Sound design: Giwgros Poulios // Music: Johann Strauss II, “An der scönen blauen Donau,” Op. 314

Dimitris Papaioannou has death on his mind. The last image in The Great Tamer, which made its New York premiere at BAM, buries itself into your gut. As if it leaped off the canvas by a Dutch master and onto the Howard Gilman Opera House stage, a vanitas of an open book, scraps of an orange, and a human skull displays a stark message. Transience is truth; decay is inevitable.

But first comes life, which unfolds as an absurdist circus set to the ambient strains of Strauss’ “The Blue Danube.” Snippets swell throughout, yet they fade after just a few measures. The expectation of a rollicking waltz lifting you up and away from thoughts of the body’s ultimate failure will be frustrated.

The Great Tamer highlights characteristic cirque acts: a stilts walker, handstand tricks, impressive balancing acts, and, memorably, a clown car where all the performers crowd onto a stool. Yet it ignores the heights-scaling, death-defying feats of the tightrope walker and the trapeze artist. Only once does a performer soar through the air on a rope. Otherwise, the preoccupation is the ground, what walks on top of it and what lurks below.

Flexible boards — taupe on one side, white on the other — overlap into a sloped floor. As if it’s a graveyard, the company of ten exhumes bodies and slips themselves into the underworld. These boards also uncover props or, once, a small water hole in which a woman bathes her feet.

A faint narrative about mastering the body emerges. An astronaut disinters a slender young man, who is as close to a protagonist as the audience will get. Bemused, he struggles to walk and understand his physical relationship to the world. At some point, he tumbles off the “floor.” Later, he reappears in a full-body cast, clutching a crutch in one hand. After a father figure of sorts chisels off the cast, our hero offers his hand to shake and then heads off on an adventure, reborn as it were.

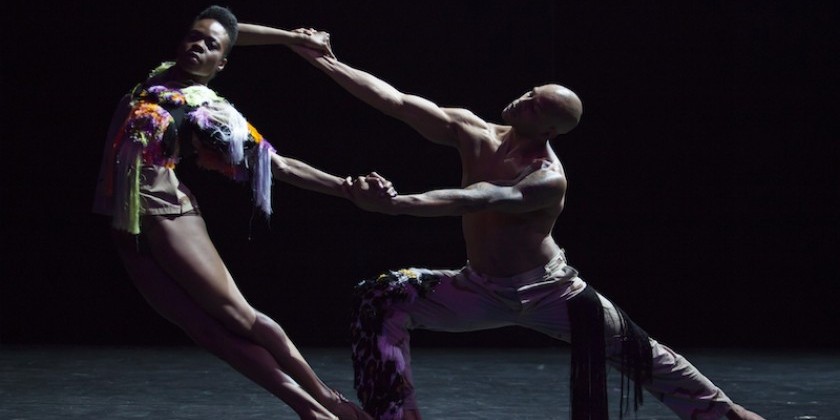

The bodies of The Great Tamer seldom have such a straightforward arc, with their many bodies assembling one body. Acting as both puppet and puppeteer, performers expose a leg or a torso from its dark clothing and then use the bare limbs to form Frankenstein-like creatures. Unforgettably, one bare-chested woman rests facing front on the coupled backside of two men, who are walking backward. After putting heels on “her” oversized feet, she spreads “her” legs wide in a lewd pose. The first time is funny, the second time is silly, but by the third iteration, I’m in the throes of existential despair. Forget time; repetition is the great tamer.

Papaioannou began as a painter before turning his attention to the stage, which means the visual imagery arrests in its clarity. The most iconic moment is a recreation of Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp. With deadpan expressions, the performers place starchy white ruffs around their neck before operating on a poor soul. They yank out pink intestines and wield terrifying silver instruments. After they complete their horror-show surgery, they set the table for a cannibalistic feast. Life is eat or be eaten.

Although the pacing feels painfully, painstakingly slow, the visual gags, many quoting or commenting on Greek mythology, come thick and fast. Golden arrows stream over the stage to pierce the floor, which are later re-contextualized as wheat. A vision of Demeter wanders through, gathering the stalks. Several half-clothed bodies evoke a centaur. Atlas holds the world aloft. Regardless of the inspiration, there is sure to be a penis or three dangling.

Near the beginning and more times throughout, a mustachioed man lolls like a sunbather on an overturned board. In a game of one-upmanship, a man covers the reposed nude body with a white cloth and then, a third blows the fabric off. Conceal, reveal, repeat. The body is doomed to cycle through the same experiences until the circle finally breaks.