IMPRESSIONS OF: jill sigman/thinkdance

The Dancer in the Dell

last days/first field a dance by jill sigman/thinkdance

Choreography: Jill Sigman ( with the performers)

Visual Design: Jill Sigman

Performed by: Hadar Ahuvia, Corinne Cappelletti, Donna Costello, Sally Hess, Irene Hsi, Paloma McGregor, Jill Sigman and Devika Wickremesinghe

Original Score created and performed by: Kristin Norderval ; Costumes by kymkym; Lighting Design: David Ferri

Plants: Camilla Hammer and Henry Sweets

Jill Sigman’s concept of choreography and dancing is larger than any stage or theatrical production. She creates, not for a single audience to clap and cheer (although I am sure she doesn’t mind a good cheer ) or to get a favorable nod --Jill creates because dance-making is her necessary response to the questions and experiences that life elicits. A soft spoken, deep thinking artist (PhD in Philosophy from Princeton) Jill Sigman choreographs the world, then invites us in (maybe for a cup of tea and a chat) to remind us that we are part of it. In her latest work last days/first field, Sigman examines our throw away environment and wonders: as the world rapidly changes, how do we change? Can we find a ritual to sustain us now?

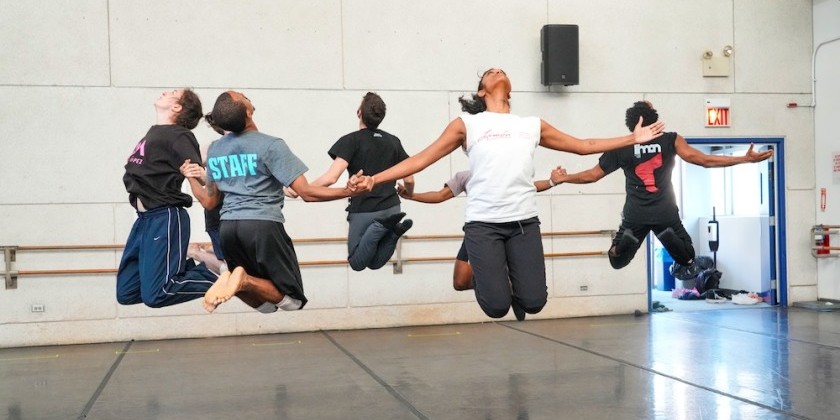

jill sigman/thinkdance last days/first field (sans costumes) Irene Hsi, Donna Costello, Hadar Ahuvia, Corinne Cappelletti Photo Rafael Gamo

Sigman’s artistic investigation has led her to look at farming, farmers and experts in the literature, economics and ethics of climate change. Just as all forms of dance involve a careful ritual in order to flower, farming too requires time and effort to yield a crop. Sigman turns to the earth itself for answers. Rugged stones, thin branches, rows of rich, dark soil and promising green sprouts of Kale are prominent characters in her work. Nature calls for our attention as much as the dancers we surround (on three sides of the stage space) at the Invisible Dog Art Center in Brooklyn.

When we meet the eight women, including Sigman, who make up the cast, we are plonked into the middle of their lives. Where are we? Compelling chanting music, a circling wail of nature sounds and women's voices, created and performed by Kristin Nordeval, carries us into an ancient tribal sensibility. Intriguing patchwork outfits, recognizable bits of present day items repurposed imaginatively and stylishly by designer kymkym, suggest to us that perhaps this group of women isn’t as ancient as it seems. Maybe we are watching people from our own time, who have lived through some sort of decimation of the world as we know it.

What does post apocalyptic movement look like? One woman’s arms gesture to the air, tenderly at first and then with increasing ferocity as if hoping to call a spirit or conjure a spell. A trio led by Paloma McGregor wakes from a deep sleep, surveys their surroundings and moves carefully as not to fall. A pair of dancers, each on a far corner, charge along a diagonal and slam into stone-like shapes before they collide. Dancers shake. They buzz like bees. They juggle the air. The gestures are fraught. They burrow their heads into one anothers' stomachs for comfort and solace and look to branches and stones to ground them. They hold on to objects of nature and imitate their energy, even burying themselves amongst the rocks and sticks. They search.

|

|

||

Throughout the melee exist two riveting constants: Devika Wickremesinghe and Sally Hess. Wickremesinghe, garbed in a gray clay colored gown, decorated with over a dozen boxes of new plantings, progresses in a slow meditative circle around the stage. Not only does she wear her plants, she carts them, balancing a “milk maid's yoke” filled with even more soil and seedlings as she travels. While riotous activity spills profusely about her, she remains calm. Wickremesinghe, off-stage, a young, charming woman, transforms with this piece. In her costume, on her path, she takes on the role of an ancient earth mother - an unyielding mountain. Her centeredness as she purposefully and simply walks is hypnotic.

Sally Hess’s shock of white silver hair might as well be a crown. Majestic in her grey green trench coat and slim, olive elastic band pants, she moves so assuredly it’s hard to tear our eyes away. We want to know her secret. Unlike Wickremesinghe, who revolves around the tribe, she is part of the group of inquisitive searchers, but is never as frantic. An elder, Hess possesses the confident cool of someone who has been through other “end of the world” events, has survived and will continue to. She has a relationship to every object she touches. She lays stones and a thin strip of grass in the center of the stage with such care and respect, the act seems its own prayer. Just as we are becoming enthralled, right in center of the stage she stands on her head. Surprise. Nothing seems to turn this woman around except her own volition.

last days/first field takes a complete turn in mood and mode after a loud bit of choreography where two sides of the audience are charged by the artists, or at least if feels that way (a bit awkward). A huge bag of soil is then carried to the center of the floor and the company (except for Hess, and Wickremesinghe, who are off in a corner creating something in a pot -we later find out it’s tea) proceed to methodically form rows of soil on the floor and carefully plant the green sprouts that were once part of the earth mother's costume. The women use 16 oz. yoghurt containers to deliberately and slowly empty the huge bag of dirt onto the stage floor. Time passes. The bag of soil is enormous and the stage is still barely covered. The lights are up. Is the show over? Do we stay in our chairs like “good” audience members.

Eventually we notice that new “green” smell of the soil, and the way the dirt breaks up. People talk to one another. I get up and walk around. The cast asks if audience members would like to sit closer to the dirt and try some kale salad. (The sprouts being planted are kale.) The person sitting next to me notices an interesting method for watering plants. Hess comes towards us and asks if we would like some tea with rosemary mint and honey.

“Yes, of course.”

These performers aren’t performers anymore but members of the community that we are all part of. All the world really is the stage, Sigman reminds us. Most of the audience moves around and chats. The others, who are still in their chairs , I wonder what they are thinking.

Choreographing the world poses its difficulties especially when you are bringing the world into a traditional performance space (yes, even lofts in Brooklyn are traditional) and beginning the experience as a “show.” Shifting from the heightened altered state of theatrical ritual, where “they’ are performers and “we” are observers, to a more casual audience participation or “Hey, let’s chat about kale and sustainable farming” is a tricky business . How can we be still feel part of a community without losing the power of performance?