IMPRESSIONS: Part II of New York City Ballet's The Robbins 100 Festival

Celebrating Jerome Robbins' Centennial

The Robbins 100 Festival

New York City Ballet

May 3-20, 2018

Lincoln Center, New York City

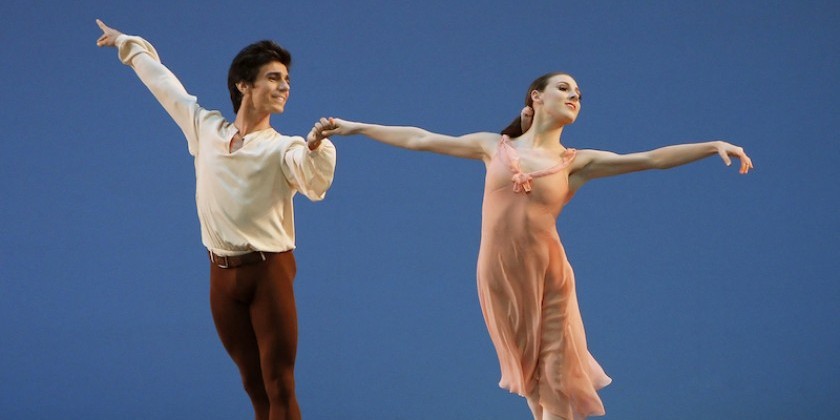

Photo: Tiler Peck and Joaquin De Luz in Dances at a Gathering; Photo by Paul Kolnik

The New York City Ballet honored Jerome Robbins with a festival this May, in the year that would have marked the choreographer’s 100th birthday. Audiences flocked to see 20 ballets in six programs for a three-week period. During weekend performances even the Fourth and Fifth-Ring tickets sold. At the end of the festival one would have gladly gone for more; and I asked myself why American Ballet Theatre did not choose to fill its house with a Robbins program. After all, Robbins, the American giant of ballet and theater, got his start both as a dancer and choreographer with what was then named Ballet Theatre. I can only hope that ABT redeems itself this fall. Imagine the excitement a joint festival of both companies would have generated for our art form.

New York City Ballet presented lots of splendid dancing supported by the fine musicianship of its orchestra, conductors, and soloists. Highlights included an evening that paired Bach’s “Goldberg Variations” from 1971 (click here for my detailed review) with Robbins’ version of Stravinsky’s “Les Noces.” If the latter was a nod to Bronislava Nijinska, then so was his In G Major from 1975. Set to Ravel, with scenery and costumes by Erté, it evoked her beachy, Chanel-designed “Le Train Bleu” from 1924.

Dances at a Gathering is a perennial classic. To the sounds of Chopin mazurkas, waltzes, and a nocturne (pianist Cameron Grant), Robbins creates many worlds of various moods and atmospheres. Solos and duets focus either on a melodic line or rhythmical intricacy; and group dances feature even or uneven numbers. Through the subtlest shifts, it is life that unfolds. A timeless community of ten individuals takes an audience on a journey. At one point all the dancers look out over the audience and marvel at an imaginary moving cloud, or bird, or apparition. One is spellbound by stillness.

Robbins’ other Chopin creations are afterthoughts. While In the Night is overly athletic and loses emotional impact, his pas de deux Other Dances, originally created for Natalia Makarova and Mikhail Baryshnikov, gives Tiler Peck and Joaquin De Luz the chance to revel in each other’s artistry. Their fancy footwork and arched backs are reasons to watch. Pianist Elaine Chelton is complicit in the dancers’ teasing phrases giving us a reason to listen. This joyful journey is too short — a complaint you do not often hear about a dance.

The theatrical Robbins easily switches from funny to ferocious. The Concert (1956), one more Chopin entry, is both hilarious and poetic. He depicts concertgoers with whimsy and creates surreal landscapes with umbrellas and butterflies. Even though a particular performance of The Cage (1951), about a hive of killer bees, may not have the sinister sting of the past, the victim ends up just as dead.

Let’s not forget about Robbins the collaborator; and I am not talking about his testimony for the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1953, but his work with composer Leonard Bernstein. The festival dedicates a program to the pair. The 1944 hit Fancy Free (which premiered at Ballet Theatre) put them both on the map; and they developed the ballet about three sailors on shore leave into the smash Broadway show “On the Town.” (For my feelings about the work that remain largely unchanged, please read my first review for The Dance Enthusiast from 2012, which was published as an Audience Review here.)

As straight-forward as the sailors are in the opening number of the Bernstein program, Dybbuk, Robbins’ stilted movement contemplation on S. Ansky’s play, based on Central-European Jewish folklore, is opaque. Robbins seems to have too much respect for the source material; and he does not allow the movement to speak for itself. The closing West Side Story Suite moves along swiftly. The entertainment factor is high, but the emotional impact gets lost in the otherwise skillful pastiche.

To me, Robbins is at his best when he portrays a state of mind with a momentary hesitation, or a relationship in the time it takes for a hand to rest on a shoulder. His insightful humanity captivates me in Afternoon of a Faun (1953), a study for two young dancers and their relationship, which exists mainly in an imaginary mirror. Their gaze is often directed toward the audience, but focused as if seeing their reflection. What an engaging and intimate little piece this is, making the audience a voyeur. The multitude of Robbins’ works require and offer very different viewing experiences. The 1979 Opus 19/The Dreamer to Prokofiev’s "Violin Concerto No. 1 in D Major"; Glass Pieces (1983), to Philip Glass; and even Interplay, which dates from 1945, in which young dancers playfully compete with one another to the jazzy score of Morton Gould, are all gorgeous worlds of their own.

A gala program includes a tribute to Robbins’ works for Broadway. Please read my colleague Erin Bomboy’s review here. Whichever world Robbins chooses to inhabit and depict, the experiences he gives us are rich, sometimes complex, and utterly rewarding. What a treat to have such fantastic dancers share Robbins’ creations with us. I am grateful we get to celebrate his birthday with a selection of his repertoire each and every year in New York City.