IMPRESSIONS: Paris Opera Ballet Dances William Forsythe & Johan Inger in 2024-2025 Season Opener

Rearray

Choreography, set and costume design: William Forsythe

Music: David Morrow

Dancers: Takeru Coste, Loup Marcault-Derouard, Roxane Stojanov

Costumes: Dorothée Merg // Lighting: Tanja Rühl //Sound Supervisor: Niels Lanz

Assistants to the choreographer: Stefanie Arndt, Ayman Harper

Blake Works I

Choreography and set design: William Forsythe

Music: James Blake

Dancers: Sarah Barthez, Léonore Baulac, Adèle Belem, Nathan Bisson, Alice Catonnet, Naïs Duboscq, Lisa Gaillard-Bortolotti, Anastasia Gallon, Margaux Gaudy-Talazac, Axel Ibot, Pablo Legasa, Germain Louvet, Hugo Marchand, Inès McIntosh, Florent Melac, Cyril Mitilian, Jérémy-Loup Quer, Silvia Saint-Martin, Roxane Stojanov, Claire Teisseyre, Jennifer Visocchi, Shale Wagman, Seojun Yoon

Costumes: Dorothée Merg, Willliam Forsythe // Lighting: Tanja Rühl, William Forsythe // Rehearsal: Stefanie Arndt, Ayman Harper

Impasse

Choreography and set design: Johan Inger

Music: Ibrahim Maalouf, Amos Ben-Tal

Dancers: Apolline Anquetil, Mathieu Contat, Lucie Devignes, Lillian Di Piazza, Letizia Galloni, Antoine Kirscher, Laurène Lévy, Marc Moreau, Francesco Mura, Fabien Révillion, Marius Rubio, Andrea Sarri, Nikolaus Tudorin, Lydie Vareilhes, Ida Viikikonski

Costumes: Bregje van Balen // Lighting: Tom Visser // Video: Annie Tådne //Rehearsal: Fernando Magadan

Three works opened the 2024-2025 season at the Paris Opera Ballet: Rearray and Blake Works I by William Forsythe and Impasse by Johan Inger.

The dancers in William Forsythe’s Rearray swerve and rebound, flicker and dart at lighting speed in unpredictable ways. Arms initiate trajectories that other body parts refuse to follow. Traditional movements distort: a soutenu turn swoops at the hips oddly, while a pirouette descends so low it seems like the dancer’s legs have corkscrewed beneath the floor. Almost every impulse, whether an arm, a leg or a direction in space, is diverted mid-route to some other destination.

Roxane Stojanov, severe, staccato and statuesque, is the focal point as Takeru Coste and Loup Marcault-Derouard seek her attention. One of the male dancers touches her shoulder and without acknowledging him, Stojanov walks away. Only when they merge into a single creature with arms connected behind their heads and backs, shape-shifting into bizarre pretzels, does she deign to join them in a dance that weaves the ordinary and extreme together.

Rearray, originally created for Sadler’s Wells Ballet in 2011 for Sylvie Guillem and Nicolas La Riche, is both beautiful and glaringly harsh. The dance is intentionally interrupted, disconnected, disjointed – like a Picasso painting digitized and shaken off the canvas to come alive in space.

Forsythe’s Blake Works I, choreographed for the Paris Opera Ballet in 2016, is set in a black void. White cylinders of light carve through the empty heights above the dancers to pool around row upon row of women with their hips pulsing. The men seem to be an afterthought, in the back row, as they join in. Long limbs costumed in celestial blue click from one pristine angle to another in ever-changing groupings, reminiscent of a Balanchine ballet.

The mellow voice of James Blake contradicts the frenetic clockwork taking place on stage. There is no touch, no interaction. Songs croon about isolation — “I’m not living here anymore” — but I am not following the singer’s words. The dancers perform with mechanical brilliance in this geometric overwhelm of arms and legs. I imagine Forsythe asking himself: How fast, how complicated, how unexpected can I make this? But I am wondering why? What is the significance?

Several moments stand out: the musicality of dancer Hugo Marchand, with his liquid upper body and sharp entrechat-six, and the intimacy between Florent Melac and Stojanov as she rolls her waist through the caress of his hands. Inès Mcintosh, Pablo Legasa and Silvia Saint-Martin carve out complicated patterns alongside, but not with, each other. In Blake Works I, the technical prowess of these dancers is astonishing, their athleticism undeniable, but my focus keeps returning to Saint-Martin.

Forsythe’s choreography demands excellent technique, extreme extension, airtight precision and the ability to perform quick reversals without showing any effort. Extremity requires a fierce center. Saint-Martin is buoyant and bright-footed. Her dancing sparkles in its precision. She seems utterly at ease, able to make this impersonal chaos look natural, playful and full of life. When Saint-Martin is dancing, ‘why’ ceases to matter.

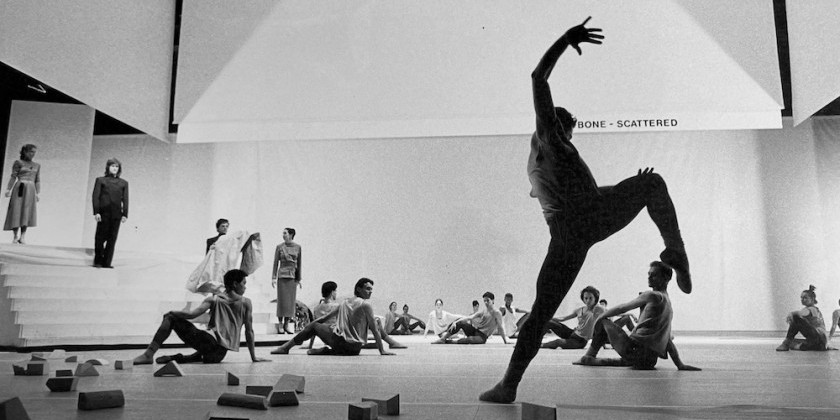

Johan Inger’s Impasse, a dance-theatre work created in 2020 for Netherlands Dance Theatre 2, is a premiere for the Paris Opera Ballet. Dancers Andrea Sarri and Marc Moreau enter through the door of a two-dimensional shed outlined in neon. Their movements are inventive, organic and vibrant. Pivoting tightly, hands fisted overhead, Sarri spins along the diagonal in exuberant ripples. Moreau, long-legged and articulate, defines grace.

Ida Viikinkoski steps out from the shed, bare-chested beneath a cape-like jacket set a-swirl with every turn and dip. The music becomes more seductive as he tempts these sweet-hearted creatures toward the risqué. A beautiful waterfall effect is created, each holding the foot of another as they fall away, one by one. A group in black joins them, adding an element of raucousness to the party. The curtain lowers slowly throughout the piece, vertically compressing the space as the cast continues to increase, carnivalesque and grotesque.

The dance starts out at high speed, rich, complex and beautiful. As the cast expands, it becomes perverted, crude and repulsive. By the end of the work, the rhythm is frantic, as the choreography becomes more simplistic and repetitive. Ghostlike shadows are projected onto the white curtain as it descends, calling to mind both flames and melting ice.

Inger believes humankind’s fascination with novelty has sent us racing to our own destruction. This topic is worthy of exploration and could not be more urgent. His vision is clear. We get his point. ‘Why?’ is simply not the question. But ‘how?’ might be. Starting out with a more moderate rhythm would provide more contrast and highlight the breakneck speed the piece ends with. Impasse could also benefit from movement sequences that evolve from simple to more complex, rather than the reverse.

Nevertheless, this work, like the two before, is deeply appreciated and well-received by the audience at the magnificent Palais Garnier opera house.