IMPRESSIONS: Ryan McNamara's "The World Premiere of a New Commission" with John Zorn at The Guggenheim

October 23, 2017

Venue: Peter B. Lewis Theater at The Guggenheim

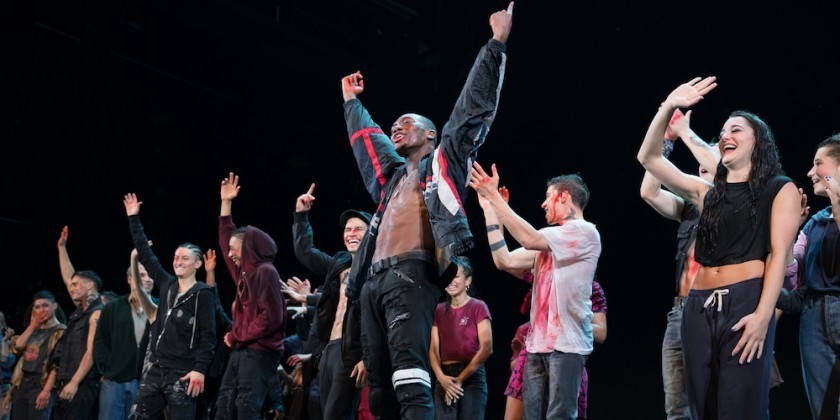

Choreography: Ryan McNamara, in collaboration with the dancers

Performers: Alex Albrecht, Dylan Crossman, Stanley Gambucci, John Hoobyar, Kyli Kleven, Frank Lombardi, India Menuez, Quenton Stuckey

Music: Commedia dell’arte, composed by John Zorn

The Guggenheim’s Works and Process is a performing arts series highlighting some of the most inspirational creators in our modern age. As its title suggests, The World Premiere of a New Commission is the latest show for the unique rotunda of the Peter B. Lewis Theater, bringing choreographer Ryan McNamara together with avant-garde composer John Zorn.

McNamara, a self-described outsider to the dance world, is more performance artist than choreographer, making cheeky, accessible work. In the case of The World Premiere, McNamara offers a compelling interpretation of Zorn’s 2016 Commedia dell’arte.

Commedia dell’arte is comprised of five movements, all of different instrumentation. The composition was inspired by the theatrical form Commedia dell’arte, a type of comedy that dates back to 16th-century Italy in which performers improvise based on predetermined scenarios. It focuses on “stock characters” like a foolish old man or a mischievous servant. Each movement of Zorn’s score represents a different archetype: Harlequin, Colombina, Scaramouche, Pulcinella, and Pierrot.

McNamara creates an appropriately goofy interpretation to highlight Zorn’s unconventional instrumental choices. Each section positions the musicians in different places, shifting our focus around the room while celebrating the beauty of the theater. The audience’s heads following the dancers and musicians feels like part of the piece itself.

15 minutes before the work’s nine p.m. start, a women costumed in colorful leggings and a baggy t-shirt unceremoniously plops herself down in the shallow orchestra pit, behind where the first group of musicians is tuning. She remains there, horizontal and immobile, until after the piece has begun.

The evening opens with “Harlequin,” set to a quartet comprised of flute, clarinet, bassoon, and viola. Like the iconic Harlequin doll depicted in The Nutcracker, the dancers enter by somersaulting and tumbling towards us, clad in sports bras and patterned neon tights.

While some of the choreography appears improvised, moments of clearly rehearsed unison materialize. The cast rings the circumference of the space, performing angular arm gestures combined with groovy hip sways and music-video motifs like a hand slapping a face. These thematic voguing motions bring to mind the jerky jointed actions of puppets or wooden dolls.

At one point, the dancers don baggy t-shirts, each printed with an image of a cast member’s face, accompanied by a name. The faces are altered to suggest the different archetypal characters, like the droopy painted eyes of the Pierrot. This motif cleverly comments on Commedia dell’arte’s stock characters; by reducing a real person to an image and a name, anyone can then portray him.

“Colombina” offers a quartet of singers on a podium at stage left. The cast poses in a montage on the stairs and then executes phrases that mirror the layered vocal lines. A moving beam of light creates a shadowy dance-club effect as the dancers become visible only when they enter the light.

Zorn represents “Scaramouche,” the proud, boastful clown, with a loud, exaggerated trio of drums, bass, and piano. The dancers emerge wearing bright skin-tight tank tops, each printed with a different made-up word, like “vilensity” or “impondism,” evoking the vocabulary of a conceited bore. In a moment that could convey self-absorption, the cast wields mini flashlights to illuminate and intently examine parts of their body.

For “Pulcinella,” an American Brass Quintet of two trumpets, a horn, trombone, and bass trombone resounds triumphantly from the balcony above us. One by one, the cast lines up against a wall to the left of the stage. A hand reaches over the wall to distribute water bottles and towels, and they drink the water in unison, like a swim team cooling down after a meet.

Throughout, our attention is divided among the musicians, the dancers, and the strange creature that’s been huddled in the orchestra pit since before the show started. During “Pulcinella,” she surreptitiously crawls from her hiding place, clutching an armful of colorful fabric pieces, which she spreads deliberately on the stairs, sorting them by color.

Finally, a quartet of four cellos portrays “Pierrot,” the sad clown. A spotlight moves around the space to highlight different members of the cast positioned throughout, and the audience looks around excitedly, wondering where the action will move next. A woman comes darting down the center aisle, draping herself dramatically over the railing separating audience from orchestra pit.

Like the beginning, The World Premiere’s ends ambiguously. The dancers pose in droopy puddles around the space, melting in aisles and dangling over railings. The musicians bow, but half of the audience has left by the time the dancers finally arise from their defeated, corpse-like ending positions.

Sometimes baffling, but always stimulating, The World Premiere of a New Work brings unconventional work to an iconic space, offering a fresh interpretation of a classic form of theater.

The Dance Enthusiast Shares IMPRESSIONS/ our brand of review and Creates Conversation.

For more IMPRESSIONS, click here.

Share your #AudienceReview of this show or others for a chance to win a prize.