IMPRESSIONS: The Joyce's Ballet Festival with Emery LeCrone, Claudia Schreier, Jeffrey Cirio, Gemma Bond and Amy Seiwert

Emery LeCrone DANCE / July 18 / In Memory; Beloved; The Innermost Part of Something; Time Slowing, Ending; Radiant Field

Claudia Schreier & Company / July 21 / Wordplay; Vigil; Solitaire; Tranquil Night, Bright and Infinite; The Trilling Wire; Charge

Cirio Collective / July 23 / Fremd, Sonnet of Fidelity, Minim, In the Mind: The Other Room, Tactility, Efil ym fo Flah (Half of my Life)

Gemma Bond Dance / July 25 / Then and Again, The Giving, Impressions

Amy Seiwert’s Imagery / July 27 / Wandering

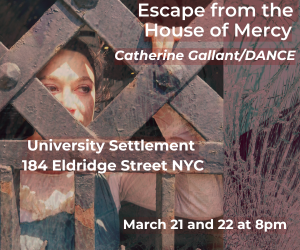

Pictured above: Stephanie Williams and company performing Gemma Bond's Then and Again at The Joyce Theater. Photo © Rod Brayman

Tradition exerts a strong pull. When the future looms opaquely, relying on proven methods is understandable, prudent even. Yet traditions must expand to accommodate new ideas. Otherwise, they calcify, existing because they’ve always existed, not because they’re relevant to the here and now.

In dance, ballet can stand for tradition. And what a tradition it is, filled with swooning beauty and technical wizardry. But audiences diversify, attitudes evolve, and ballet must reflect that while still staying, discernibly, ballet. Choreographers of ballet have the exhilarating — and daunting — mission of choosing what to add, subtract, or preserve.

The Joyce Theater celebrates five clearly articulated visions with Ballet Festival. Designed to introduce audiences to choreographers who create work outside of large companies, the twelve-day event features four female and one male choreographers — a refreshing ratio in a world where the dance makers are overwhelmingly male.

Three of them receive their Joyce debut (Claudia Schreier, Jeffrey Cirio, and Gemma Bond) while two return (Emery LeCrone and Amy Seiwert). Regardless of their experience, all believe in the relevance of ballet to the 21st century. The question is: Do we?

Russell Janzen & Stephanie Williams in Emery LeCrone's Partita No. 2 in C Minor. Photo by Matthew Murphy.

Emery LeCrone draws ballet from heaven to earth with five languid tone poems: a solo tentatively danced by her sister, Megan Le Crone, a soloist with New York City Ballet; a luscious pas de deux for Cory Stearns and Stephanie Williams of American Ballet Theatre; and three mellifluous group works performed by her titular company.

LeCrone destabilizes ballet’s verticality by weighting the phrases. Spines ripple and elbows undulate, each action seemingly commenced and concluded from the breath. Transitions between low-slung arabesques and step-over turns are subtle, almost pedestrian, featuring small steps, port de bras where the arms extend halfway, brief pauses with the head cocked downward. The result is introspection, moodiness, the quintet of pieces bleeding together into one extended daydream.

Claudia Schreier fetishizes ballet’s virtuosity in six works that flaunt some of New York’s finest dancers: Unity Phelan and Jared Angle of New York City Ballet, the endlessly charming Da’Von Doane of Dance Theatre of Harlem, and former ballerina-turned-contemporary-dance-aficionado Wendy Whelan. Save the teeming Charge for seventeen performers, the works are small but lively, with Schreier showing zeal for pas de deux.

Schreier’s phrases sizzle with razzmatazz as men hoist split-legged women in the air; men jog around women who have legs hooked in attitudes; and men grasp women with two hands to pull them this way and that. Often, it reads as graceful cheerleading save The Trilling Wire, a skittering solo for the luminous Whelan, which looks like it was choreographed by someone else. While each piece glimmers with subtlety — interlocking arms that form an infinity symbol, a lunge with fluttering arms — too soon, frenzied bravado overwhelms them.

Jeffrey Cirio hides ballet’s formalism beneath a slinky aesthetic. As Cirio Collective, he presents four works choreographed by himself, one film directed by Sean Meehan (also choreographed by Cirio), a lyrical pas de deux by Paulo Arrais, and a sprawling duet by Gregory Dolbashian for Cirio and Blaine Hoven. The dancers, many of whom are former colleagues from Boston Ballet and current ones from American Ballet Theatre where Cirio is a principal, perform with stank faces.

Cirio sends his dancers slipping and sliding in socks through dim lighting and ambient music. The pretzel-like sequences are incessantly frontal as if Cirio choreographed them while staring at himself in the mirror. Sometimes, it appears he doesn't know what to do with his cast when they’re not dancing, so he stations them in the back, like sentries. One time, a performer flits offstage as if he just nailed a classical ballet variation — a jarring sight amidst the music video angst. The larger issue is the rabid start-and-stop dynamics. When the heat is turned up this high, the coolness acts as an effect rather than an attitude.

Gemma Bond humanizes ballet. In two group pieces and one pas de deux, she eschews grandiose gymnastics for delicate, swirling geometry. Performed by her colleagues at American Ballet Theatre, the company with which she has danced since 2008, the quality is pin bright.

Bond makes the negative space eloquent with pirouettes decorated with low passés and jumps that zip rather than peak. Thus, the music (some strings, a little electronica) gushes in and elevates the actions from postural to sculptural. Her works tease out motifs like arms lifted as a touchdown sign where elbows soften or wrists waver, a first arabesque in profile, seen afresh when personalized by different dancers. The pieces are classical, yet so natural, so honest that it feels like commentary on bodily integrity. While Bond’s craftsmanship (which has improved in its use of orientation and pathways) is sound, her gift is casting a mood that holds us rapt, wishing it would never end.

Amy Seiwert emphasizes the landscaping aspects of ballet. Under the banner of her company Imagery, she offers the sole full-length work of the festival — Wandering. Inspired by Schubert’s Winterreise, twenty-four stultifying songs for tenor and piano, she investigates the travails of traveling. Four men and four women take turns as a globetrotting protagonist, pulling on and off a red jacket. The first act shows the dancers in white costumes against a black background; in the second, the colors switch, like the negative of a photograph.

Seiwert excels at gorgeous tableaux: three couples crimped in the fetal position, one on top of the other; a clump of dancers with arms outstretched, fingers gnarled like broken twigs. As a whole, though, Wandering is overwrought, episodic, and lasting far beyond its natural potential. Without forward momentum, from neither the music nor the emotional arc, the initial intrigue melts into ennui early on.

The hearty attendance and enthusiastic reception (each choreographer received, at the minimum, a partial standing ovation) should point to ballet’s robust future. I, however, remain unconvinced. While the choreographers present superficially slick zeitgeists, taken as one argument, their interpretation is conventional and too timid.

That's because tropes abound: firmly delineated gender roles, prettiness, an overreliance on pas de deux, abstraction, tediously melodic music. Yet tantalizing hints appear — LeCrone’s use of gravity, Bond’s positioning of ballet as morality, Seiwert’s dioramas — suggesting the potential for ballet to be as important to the future as it was to the past. But manifesting that potential will require boldness, a willingness to buck tradition.