IMPRESSIONS: European Perspectives — Tero Saarinen Company, Compagnie Maguy Marin, and Dresden Semperoper Ballett at The Joyce Theater

October 11, 2017 / Tero Saarinen Company / Morphed

October 18, 2017 / Compagnie Maguy Marin / BiT

November 2, 2017 / Dresden Semperoper Ballett / Artistic Director: Aaron Sean Watkin / Choreography: Stijn Celis (Vertigo Maze), David Dawson (5 and On the Nature of Daylight), Joseph Hernandez (Ganz Leise Kommt Die Nacht/The Night Falls Quietly)

Pictured above: Tero Saarinen Company in Morphed.

Whether you like it or not, the world is getting flatter, to use the metaphor Thomas L. Friedman employed in his bestselling book that analyzed the spread of globalization. Information can be exchanged easily and frequently, often with the messenger having no idea where his, her, or their message will land.

In dance, where the medium skews to the visual, new works appear daily on platforms like YouTube and Instagram. You can fall down a rabbit hole watching video after video of pieces you’ve never seen by choreographers you’ve never heard of.

This acts as a marked change from a decade or so ago. While dance didn’t develop in isolation, news took longer to wind its way around the world. Now, with borders virtually erased, dance acts and reacts to itself, raising the question if where work is made influences what kind of work is made.

For three weeks this fall, The Joyce Theater hosted a trio of companies from Europe, bringing this question to the forefront of my mind. Tero Saarinen Company (Finland), Compagnie Maguy Marin (France), and Dresden Semperoper Ballett (Germany) have little overlap in substance and style. Their programs, however, suggest that, underneath the gloss and fervency that characterizes much contemporary dance, the world is not flat.

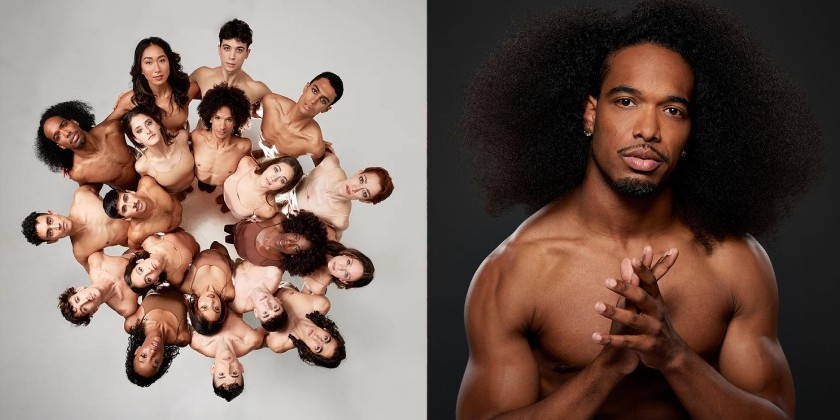

Saku Koistinen (left), Ima Iduozee and Jarkko Lehmus in Morphed. Photo: Heikki Tulli ©

In the beginning, Tero Saarinen Company’s Morphed doesn’t look like anything you haven’t seen before. Against a perimeter of dangling ropes, seven men pace and swivel in sharp directional changes. Horns wail. The black-hooded men freeze in a line to resemble a convocation of Death Eaters.

But the piece expands, first physically and then contextually. The septet slashes their arms and flings their legs as the score, three blaring symphonies by Esa-Pekka Salonen, threatens to consume them. They gradually remove items of clothing, seguing from anonymity to individuality in a display of the truth. Some are older with gray hair or no hair. Some aren’t great with little turnout or no turnout. These guys are a scrappy bunch.

As the dance becomes more demanding, more heated, the men perform as if their life depends on it. Because this isn’t a typical piece where men flaunt their technical aptitude — virtuosity their defense against the charges of homosexuality or femininity or eccentricity lodged at men who dance.

Morphed is an exercise in male vulnerability, the stage a safe place where men can exhibit their bodies in all their messy, fleshy imperfection. It’s as unusual as it’s welcome in America where our society polices the male body from performing anything other than stoicism and competency.

Compagnie Maguy Marin in BiT. Photo: Herve Deroo ©

In the beginning, Compagnie Maguy Marin’s BiT doesn’t look like anything you haven’t seen before. Three men and three women attired in homespun fashions of slouchy jackets and knee-length skirts weave up, down, and around a half-dozen ramps. While holding hands, the sextet joyously stamps and grapevines in a derivation of the farandole. They’re just folks dancing.

Then, social protocol breaks down in this mini Eden. The dancing becomes wilder: clapping hands, bumping hips, a mini mosh pit. Despite the chaos, the chain reforms in the midst of the pitched gaiety until a man sexually assaults a woman. The group splinters.

For the next hour, this micro-society will attempt to secure its morality by progressing through western civilization’s social systems. Pagans indulge their libidinous urges, the Greek Fates wield spindles, monks ritualistically rape a chosen one, and upper-crust party animals can’t save one of its own from throwing herself off a ramp to avoid sexual harassment. Through these scenarios, all set to seething electronica by Charlie Aubry, the six performers revisit the folk dancing sequence — the calm before the inevitable storm.

Finally, the six dancers arrive in present time as good little worker bees. In a Sisyphean task, they crawl up the ramps only to slide back down. Once, they reach the top, one by one, they catapult themselves into the abyss, their reward uncertain. Lights out — the world has ended, and no one onstage seems the better for having been in it.

Marin’s message is bleak and accusatory. Corruption, usually by men, will breach any ethical system upon which society founds itself. Like an endless helix, the cycle will continue — same song and dance, different costumes. It’s not the sanguine message most Americans want to hear, but in Marin’s hands, it rings of the truth.

Gina Scott, Alice Mariani, Zarina Stahnke and Michael Tucker in David Dawson's 5 at The Joyce Theater. Photo © Yi-Chun Wu.

In the beginning, Dresden Semperoper Ballett’s program doesn’t look like anything you haven’t seen before — a mixed bill of two classical (pointe shoes, applause-garnering pirouettes) and two contemporary (stank faces, complicated gestural sequences) works. Using a minimal palette of hazy lighting, a black backdrop, and diaphanous costumes, the company boasts technical chops that swerve from pirouettes a la seconde to the postures of a dilapidated puppet.

Choreographer David Dawson contributes 5 (from his Giselle), a romp of buttery academicism, and On the Nature of Daylight, a billowing duet to Max Richter’s schmaltzy number of the same name. Dawson maintains the hallmarks of ballet elegance, yet he softens its rigid contours with skids en pointe and quirky transitions of fast-flying feet.

The other numbers, however, lack Dawson’s cleverness. To what sounds like smooth jazz from the underworld, two men and two women in Joseph Hernandez’s Ganz Leise Kommt Die Nacht/The Night Falls Quietly waver and quaver like teenagers in fits of angst. Stijn Celis’ Vertigo Maze unfolds like a baroque music video, all Bach, powdered skin, and cryptic couplings.

As the evening — pleasant, sometimes impressive — continues, one thing becomes apparent. Dresden Semperoper Ballett demonstrates a well-articulated visceral thesis. No matter the aesthetic, the dancers lift their chins and flourish their wrists and magnify verticality, whether in the air or on the floor. Maybe it’s performing in that magnificent theater the company calls home, but its emphasis on projecting up and out embodies ballet’s ability to give us something in which to believe. In America, where many things feel broken, it’s fortifying to remember that ballet, in its moment, can transcend our moment.

The Dance Enthusiast Shares IMPRESSIONS/ our brand of review and Creates Conversation.

For more IMPRESSIONS, click here, including our IMPRESSIONS of The Joyce's 2017 Ballet Festival.

Share your #AudienceReview of this show or others for a chance to win a prize.