IMPRESSIONS: "In Violent Circles (The Rite of Spring)"

IMPRESSIONS: In Violent Circles (The Rite of Spring)

Riedel Dance Theatre -March 7, 2013 at the Ailey Citigroup Theater

Choreography Jonathan Riedel

Dancers Joshua Arnold, James Brenneman III, Louis Chavez, Hana Ginsburg, Julia Kelly, Madisyn Maniff, Cleo Sykes

Composer Igor Stravinsky rearranged by Neil Alexander

Costumes Roxane D' Orleans Juste

March 23, 2013

Christine Jowers for The Dance Enthusiast

As Igor Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring celebrates its 100th birthday, Jonathan Riedel adds his name to the list of choreographers sharing their interpretations of the work. A century ago in Paris, shocked patrons of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées rioted over the carnality in Stravinsky’s shifting tones and metres, as well the vulgarity of the angular, un-balletic moves in Valsav Nijinsky’s ballet. Nothing like it had been seen or heard before. Fights broke out between haters and lovers of the work. Police were called. Stravinsky supposedly escaped the theater before the piece was finished.

All was safe on Thursday, March 7th when Riedel Dance Theatre presented In Violent Circles (The Rite of Spring) to a packed crowd at The Ailey Citigroup Theater. Even though the subject was a ghastly tale of rape and murder (based on a 13th century folk ballade Töres dottrar i Wänge), the performance's most controversial aspect (and perhaps only for music critics) may have been that The Rite of Spring, played live, was not Stravinsky’s orchestral version, but rather a rearrangement for solo piano by jazz pianist, Neil Alexander. A brave undertaking. Alexander played remarkably with power. One could scarcely believe that the man had only two hands.

Today, telling a tale simply (with moving bodies, dressed in black, on a bare stage, using a few small props) may seem shocking because contemporary choreographers don't typically take on narrative work. It harkens back to classic modern dance -not very experimental- and, at its worst can seem cornball or cheesy. (Ugh.) Unadorned narrative is challenging, though. With nothing to hide behind, the choreography, direction and dancing is ALL you see; if there is no craft or skill, it is evident immediately. Thankfully, Jonathan Riedel is an adroit author of movement stories. He composes his stage and his dancers’ actions with utmost economy and intelligence using distinct geometry, simple movement vocabulary, musicality and constant motion to keep our imagination awake and absorbed in the happenings on stage. In this new piece, his fine dancers offer the shading to their choreographers’ black and white palette, capturing us with their qualitative choices and ear for music.

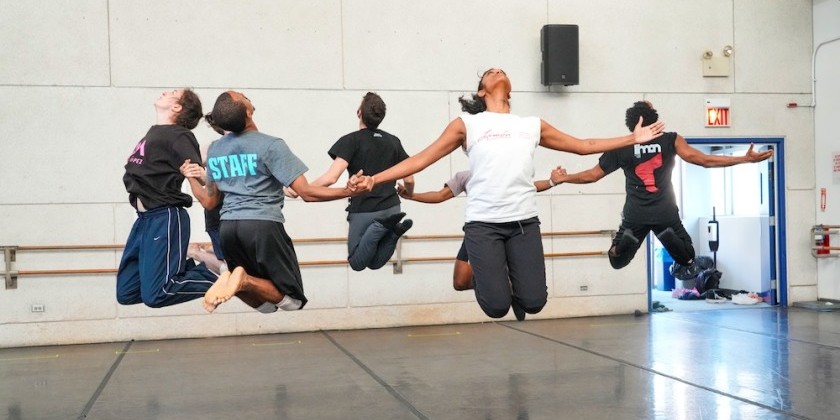

In Violent Circles (The Rite of Spring) centers on the interactions of two groups - a loving, bustling family: The Mother, Julia Kelly; The Father, James Brenneman III; The daughters, Madisyn Maniff and Cleo Syeks and The Outsiders: Joshua Arnold, Louis Chavez and Hana Ginsburg - a disreputable band whose every step reveals them to be unctuous, malevolent leeches.

We are taken from the morning meal - where the mother stirs up food in a big white bowl and the father blesses his children with three loving thumps to their upper bodies - through to the silly arguments of two highly energetic “teenage?” girls as they prepare to go out into the world for the day. There is an upright goodly spirit to the action. When the family moves together, they wind in a circle, gently turning as if part of folk dance. If they are not dancing as a group, they spin off in whirlwinds creating their own little loops of energy which we feel certain will eventually come together in reassuring harmony.

Darkness creeps in with the three outsiders. While the trio may leap and partner using similar movement to that of the family, their manic approach suggests nothing good can from their actions. And nothing good does. Upon meeting the gang, the girls are eventually murdered. Still, the stylized killing, with its unapologetic aggressors - who saunter off glibly after their deed is done- is not quite as upsetting as The Mother's (Kelly's) solo as she waits for her daughters to return home.

The movement before that point had been large, circular and sweeping, but Riedel’s clear change of spatial design and shift to an inward focus pulls at us. Kelly, impatient and concerned, dances on an urgent angle, away from center stage. She barely stirs, but every fiber of her being is in panic. She reaches out to find her girls, and then recedes towards her husband who tries to reassure her that all is well. From tiny, anxious gestures and a comforting hug emerges an exasperated tossing and flinging duet, which reveals the harshness of an inner world that will never know harmony again.

Perhaps the well-choreographed despair of a mother losing her children won't cause riots in the streets, but it still can make hearts stop.

All was safe on Thursday, March 7th when Riedel Dance Theatre presented In Violent Circles (The Rite of Spring) to a packed crowd at The Ailey Citigroup Theater. Even though the subject was a ghastly tale of rape and murder (based on a 13th century folk ballade Töres dottrar i Wänge), the performance's most controversial aspect (and perhaps only for music critics) may have been that The Rite of Spring, played live, was not Stravinsky’s orchestral version, but rather a rearrangement for solo piano by jazz pianist, Neil Alexander. A brave undertaking. Alexander played remarkably with power. One could scarcely believe that the man had only two hands.

|

| James Brenneman III and Hana Ginsburg in In Violent Circles, (The Rite of Spring) Choreography by Jonathan Riedel ; Photo © Jonathan Beck |

Today, telling a tale simply (with moving bodies, dressed in black, on a bare stage, using a few small props) may seem shocking because contemporary choreographers don't typically take on narrative work. It harkens back to classic modern dance -not very experimental- and, at its worst can seem cornball or cheesy. (Ugh.) Unadorned narrative is challenging, though. With nothing to hide behind, the choreography, direction and dancing is ALL you see; if there is no craft or skill, it is evident immediately. Thankfully, Jonathan Riedel is an adroit author of movement stories. He composes his stage and his dancers’ actions with utmost economy and intelligence using distinct geometry, simple movement vocabulary, musicality and constant motion to keep our imagination awake and absorbed in the happenings on stage. In this new piece, his fine dancers offer the shading to their choreographers’ black and white palette, capturing us with their qualitative choices and ear for music.

In Violent Circles (The Rite of Spring) centers on the interactions of two groups - a loving, bustling family: The Mother, Julia Kelly; The Father, James Brenneman III; The daughters, Madisyn Maniff and Cleo Syeks and The Outsiders: Joshua Arnold, Louis Chavez and Hana Ginsburg - a disreputable band whose every step reveals them to be unctuous, malevolent leeches.

|

| Madisyn Maniff , Cleo Syeks, and Joshua Arnold In Violent Circles, (The Rite of Spring) Choreography by Jonathan Riedel ; Photo © Jonathan Beck |

We are taken from the morning meal - where the mother stirs up food in a big white bowl and the father blesses his children with three loving thumps to their upper bodies - through to the silly arguments of two highly energetic “teenage?” girls as they prepare to go out into the world for the day. There is an upright goodly spirit to the action. When the family moves together, they wind in a circle, gently turning as if part of folk dance. If they are not dancing as a group, they spin off in whirlwinds creating their own little loops of energy which we feel certain will eventually come together in reassuring harmony.

Darkness creeps in with the three outsiders. While the trio may leap and partner using similar movement to that of the family, their manic approach suggests nothing good can from their actions. And nothing good does. Upon meeting the gang, the girls are eventually murdered. Still, the stylized killing, with its unapologetic aggressors - who saunter off glibly after their deed is done- is not quite as upsetting as The Mother's (Kelly's) solo as she waits for her daughters to return home.

|

||

Perhaps the well-choreographed despair of a mother losing her children won't cause riots in the streets, but it still can make hearts stop.