IMPRESSIONS: Faye Driscoll

"There is so much mad in me" at Dance Theater Workshop, Wednesday March 31, 2010

Betsy England 2010

After a near blackout, the entire theater flooded with bright white light, leaving the audience squinting uncomfortably. Jacob Slominski strode about the stage with a heavy flashlight and screamed, “Get down! Get the fuck down!” at his fellow performers lying face down on the stage with their arms behind their backs. He came up the steps into the audience and yelled at a man on the aisle to get on the floor. The man assumed the common attitude of the audience participant, half in on the joke and half afraid of being the butt of the joke, and looked back at Jacob defiantly. Jacob responded by threatening to beat him with the flashlight. Being three seats away and reminding myself that this was “just” a performance did not stop my heart from racing or my palms from sweating.

Faye Driscoll’s There is so much mad in me deals with mob mentality and brutality and the performance depicts different versions of each. In the beginning, Lindsay Clark is ostracized from a circle of happily chatting performers. As she approaches the laughing group, they fall silent and avoid eye contact with her. Adaku Utah is wonderful, first as Tyra Banks on America’s Next Top Model and then as Oprah Winfrey, informing us that we have all won a brand new car. For that moment, we were the mob as we collectively fluttered in the excitement of such prospects.

In a memorable passage, the entire cast of nine, positioned in a grid facing front, jumps rapidly in unison-- and on nearly straight legs -- to a driving beat. The lights switch swiftly from red to green to blue. A corps of ballet dancers couldn’t have achieved more perfect synchronicity, and they definitely wouldn’t have looked as menacing.

In fact, the performers and the choreography were impressive throughout. Early on in the performance, Clark and Jesse Zaritt on either side of Michael Helland, lift him by his horizontally outstretched arms, and run in a large circle. He looks like a deer as his body skims across the floor – his legs taking large, bounding strides.

The trio sets themselves for a collision course with the wall. Their momentum propels Helland up it, climbing hand over hand up a vertical pipe. Crumpling at the bottom of the pipe, Zaritt sitting on Helland’s back, and Clark lying on the ground, Clark inches an articulate, flexible foot up Zaritt’s body until she tickles his armpit. Then, Clark and Helland carried Zaritt, as if he is sitting in a chair, running him straight into the back brick wall of Dance Theater Workshop. Instead of crashing into it, though, he runs up it with the other two supporting his shoulders. These moments are beautiful.

In the pre-show discussion with Kristin Marting and Kim Whitener of HERE Arts Center, it was explained that in creating her works, Driscoll mines each performer’s experiences, pulls out his viscera, and incorporates them into the piece. Although it is impossible to tell which sketch corresponded to which artist, the scenarios, ranging from fights with significant others to scenes on talk shows, would have been painful in real life. It cannot be an easy process, and I doubt beauty and craft are adequate rewards. They are in service to something else, but the question remains: what is that something else?

After Slominski stops bullying both the other performers and the audience with his flashlight, Clark slowly gets up and begins to sing a song. One by one, the others rise and join her until they are all standing in a line, facing the audience. “This is what it looks like when God is all around,” they sing. I was not the only one in the audience who thought this was the end. It looked like either an ironic comment about those who believe God is all around despite traumatic events, or a redemptive moment where victims rise and sing together. Either one would have been easily digestible, but Driscoll soon plunged us into another sketch. While she avoided creating just another piece about irony or redemption, it’s hard to tell what she did create.

Some art is intended to make us more aware of our surroundings and ourselves. I suspect this was also Driscoll’s intent, and yet I am still struggling to productively apply the negative feelings I experienced during her performance to my awareness outside the theater. What is the point of making your audience feel threatened?

After a near blackout, the entire theater flooded with bright white light, leaving the audience squinting uncomfortably. Jacob Slominski strode about the stage with a heavy flashlight and screamed, “Get down! Get the fuck down!” at his fellow performers lying face down on the stage with their arms behind their backs. He came up the steps into the audience and yelled at a man on the aisle to get on the floor. The man assumed the common attitude of the audience participant, half in on the joke and half afraid of being the butt of the joke, and looked back at Jacob defiantly. Jacob responded by threatening to beat him with the flashlight. Being three seats away and reminding myself that this was “just” a performance did not stop my heart from racing or my palms from sweating.

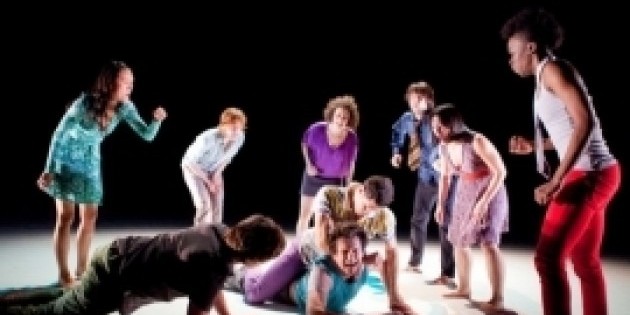

There is so much mad in me - Faye Driscoll and Company at Dance Theater Workshop- Photos by Yi Chun Wu |

Faye Driscoll’s There is so much mad in me deals with mob mentality and brutality and the performance depicts different versions of each. In the beginning, Lindsay Clark is ostracized from a circle of happily chatting performers. As she approaches the laughing group, they fall silent and avoid eye contact with her. Adaku Utah is wonderful, first as Tyra Banks on America’s Next Top Model and then as Oprah Winfrey, informing us that we have all won a brand new car. For that moment, we were the mob as we collectively fluttered in the excitement of such prospects.

There is so much mad in me - Faye Driscoll and Company at Dance Theater Workshop- Photos by Yi Chun Wu |

In a memorable passage, the entire cast of nine, positioned in a grid facing front, jumps rapidly in unison-- and on nearly straight legs -- to a driving beat. The lights switch swiftly from red to green to blue. A corps of ballet dancers couldn’t have achieved more perfect synchronicity, and they definitely wouldn’t have looked as menacing.

In fact, the performers and the choreography were impressive throughout. Early on in the performance, Clark and Jesse Zaritt on either side of Michael Helland, lift him by his horizontally outstretched arms, and run in a large circle. He looks like a deer as his body skims across the floor – his legs taking large, bounding strides.

There is so much mad in me - Faye Driscoll and Company at Dance Theater Workshop- Photos by Yi Chun Wu |

The trio sets themselves for a collision course with the wall. Their momentum propels Helland up it, climbing hand over hand up a vertical pipe. Crumpling at the bottom of the pipe, Zaritt sitting on Helland’s back, and Clark lying on the ground, Clark inches an articulate, flexible foot up Zaritt’s body until she tickles his armpit. Then, Clark and Helland carried Zaritt, as if he is sitting in a chair, running him straight into the back brick wall of Dance Theater Workshop. Instead of crashing into it, though, he runs up it with the other two supporting his shoulders. These moments are beautiful.

In the pre-show discussion with Kristin Marting and Kim Whitener of HERE Arts Center, it was explained that in creating her works, Driscoll mines each performer’s experiences, pulls out his viscera, and incorporates them into the piece. Although it is impossible to tell which sketch corresponded to which artist, the scenarios, ranging from fights with significant others to scenes on talk shows, would have been painful in real life. It cannot be an easy process, and I doubt beauty and craft are adequate rewards. They are in service to something else, but the question remains: what is that something else?

There is so much mad in me - Faye Driscoll and Company at Dance Theater Workshop- Photos by Yi Chun Wu |

After Slominski stops bullying both the other performers and the audience with his flashlight, Clark slowly gets up and begins to sing a song. One by one, the others rise and join her until they are all standing in a line, facing the audience. “This is what it looks like when God is all around,” they sing. I was not the only one in the audience who thought this was the end. It looked like either an ironic comment about those who believe God is all around despite traumatic events, or a redemptive moment where victims rise and sing together. Either one would have been easily digestible, but Driscoll soon plunged us into another sketch. While she avoided creating just another piece about irony or redemption, it’s hard to tell what she did create.

There is so much mad in me - Faye Driscoll and Company at Dance Theater Workshop- Photos by Yi Chun Wu |

Some art is intended to make us more aware of our surroundings and ourselves. I suspect this was also Driscoll’s intent, and yet I am still struggling to productively apply the negative feelings I experienced during her performance to my awareness outside the theater. What is the point of making your audience feel threatened?

FOOTNOTES

Other Perspectives on There is so much mad in me and Faye Driscoll

http://www.villagevoice.com/2010-04-06/dance/faye-driscoll-is-mad-at-you-and-you-and-you/

http://www.thirteen.org/sundayarts/blog/blog/theater/there-was-so-much-feeling-in-this

http://www.dance-enthusiast.com/features/75/

Other Perspectives on There is so much mad in me and Faye Driscoll

http://www.villagevoice.com/2010-04-06/dance/faye-driscoll-is-mad-at-you-and-you-and-you/

http://www.thirteen.org/sundayarts/blog/blog/theater/there-was-so-much-feeling-in-this

http://www.dance-enthusiast.com/features/75/