IMPRESSIONS: Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (All New Program)

New York City Center- December 29th, 2009

Dancing Spirit (2009)

Choreography: Ronald K Brown

Music: Duke Ellington, Winton Marsalis, Radio head, War

Costumes: Mooted Wunmi Olaiya

Lighting: Clifton Taylor

In/Side (2008)

Choreography: Robert Battle

Music: Nina Simone

Lighting: Burke Wilmore

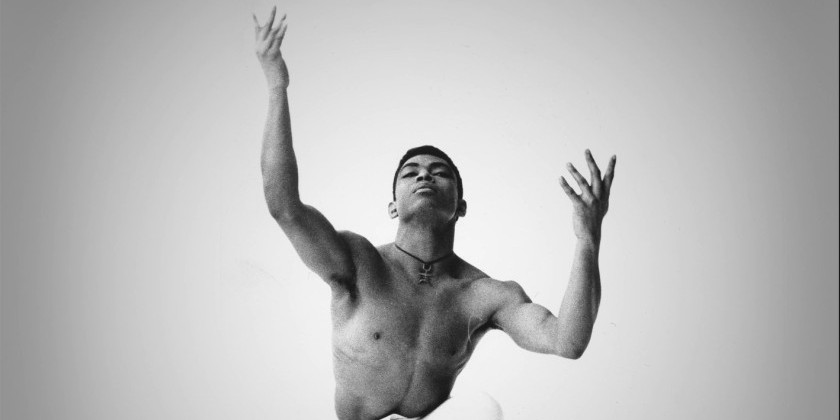

Performer: Samuel Lee Roberts

Among Us - Private Spaces: Public Places (2009)

Choreography and Original Artwork: Judith Jamison

Original Music: ELEW

Costumes: Paul Tazewell

Lighting and Scenic Design: Al Crawford

Uptown (2009)

Choreography: Matthew Rushing

Script: Matthew Rushing and Gregor L. Gibson

Music and Historical Text: Paul Robeson Jr., Fats Waller, W.E.B DuBois, Zora Neale Hurston, Johnny Alston, Lee Norman, Eubie Blacke and Noble Sissle, Langston Hughes

Original Music: Ted Rosenthal

Costume Concept and Design: Matthew Rushing

Lighting and Scenic Design: Al Crawford

Photographs: Various artists

Choreography: Ronald K Brown

Music: Duke Ellington, Winton Marsalis, Radio head, War

Costumes: Mooted Wunmi Olaiya

Lighting: Clifton Taylor

In/Side (2008)

Choreography: Robert Battle

Music: Nina Simone

Lighting: Burke Wilmore

Performer: Samuel Lee Roberts

Among Us - Private Spaces: Public Places (2009)

Choreography and Original Artwork: Judith Jamison

Original Music: ELEW

Costumes: Paul Tazewell

Lighting and Scenic Design: Al Crawford

Uptown (2009)

Choreography: Matthew Rushing

Script: Matthew Rushing and Gregor L. Gibson

Music and Historical Text: Paul Robeson Jr., Fats Waller, W.E.B DuBois, Zora Neale Hurston, Johnny Alston, Lee Norman, Eubie Blacke and Noble Sissle, Langston Hughes

Original Music: Ted Rosenthal

Costume Concept and Design: Matthew Rushing

Lighting and Scenic Design: Al Crawford

Photographs: Various artists

Yes, Samuel Lee Roberts’ performance was dramatic, but it was subtle and specific allowing us to enter the soul of the ballet...

...While no choreographer brought it all together, Battle’s In/Side was the most enjoyable.

© GillianVinton 2009...While no choreographer brought it all together, Battle’s In/Side was the most enjoyable.

The “All New” program presented by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater introduced four very different takes on Ailey’s legacy. Ronald K. Brown, Robert Battle, Matthew Rushing and Judith Jamison presented new ballets that illustrated their unique views of the company’s past, present, and future.

The evening started with Ronald K. Brown’s Dancing Spirit. A single man, Matthew Rushing, standing upstage, begins a slow, measured, linear phrase moving towards the downstage diagonal. A vibraphone rendition of Duke Ellington’s “The Single Petal of a Rose” floats over the scene as Renee Robinson enters behind Rushing repeating the same choreography. As they progress forward, one dancer steps into place behind them, and then another, and so on, until a line of six people, all repeating the same choreography, stretches across the stage.

When Rushing reaches his destination, he breaks off into a solo that reveals Brown’s African influences. He “ clears the way” with reaping motions traditionally used to praise the god Elegua, a Yoruba deity often referred to as the god of beginnings.

In an interview with “TimeOut/NY”, Brown described his ballet as loosely following the trajectory of the Ailey Company: Alvin Ailey here represented by Rushing, and Judith Jamison represented by Robinson.

In the first few minutes of Dancing Spirit, Rushing establishes a strong movement base with Robinson following close in his footsteps. Group dances, diving more deeply into African and Afro-Cuban movement, follow. The artistry of the company is given a chance to shine as the dancers simply walk in place, shifting their weight while swinging their hips and shoulders. The women spin with their arms curved upwards and the men’s spines undulate as they bend low to the ground. To complete the story, Rushing’s Ailey character steps back into the shadows making way for a powerful solo by Robinson, the Jamison character.

Robinson is a force to be reckoned with as she sweeps the earth with her skirts and the sky with her arms in a solo inspired by Yemaya, the Yoruba goddess of all creation. As she ends her dance, the company re-enters to finish with a rousing, sassy, finger-wagging number that continues the metaphor of Ailey’s trajectory by showing off the unified spirit that has brought the company to where it stands today.

Brown, not relying on technical showstoppers or exaggerated emotions, allows the integrity of the dancers artistry to shine. His work is stronger for it.

This was not the case in Judith Jamison’s world-premiere, Among Us (Private Spaces: Public Places). The idea behind the ballet is that the dancers are characters in a gallery who have their inner dialogues revealed through the intervention of the Jin (Genie) played by Clifton Brown. Brown’s opening solo features moves from traditional Bharatanatyum Indian dance with a lot of fancy balances and leg extensions. Unfortunately, the other characters “private” vignettes are so literal, dramatic and obvious; it is difficult to take them seriously. There is the clichéd “lost love” story, danced by Matthew Rushing and Ronnie Favors; a stab at President Obama, danced by Jamar Roberts; three drunken buffoons cat-calling women and falling all over each other; and, the worst of all, Linda Celeste Sims reduced to playing a “sexy wild woman” to Glenn Allen Sims’ “playboy”. Celeste Sims never stopped twirling and twitching her arms around her head through the whole duet. By the finale, I was aching for some nuance; instead Jamison gave us a dance party extravaganza with disco music and gold glitter falling from the ceiling.

To Jamison’s credit, Among Us... did show off the dancers’ ferocious technique with some of the most difficult choreography I’ve ever seen. There were pitch turns into arabesques, dramatic balances, and impressive leg extensions, but without the dancers over-the-top emoting, none of her story would have come through.

In/Side, a solo choreographed by Robert Battle, was also highly emotive, but about as different from Jamison’s work as could be. In In/Side the emotion comes from within the choreography instead of being slathered on top. Yes, Samuel Lee Roberts’ performance was dramatic, but it was subtle and specific, which allowed us to enter the soul of the ballet. There was fear, as he retreated from an imaginary foe and audibly gasped; wild abandon, shown in a series of fast, furious jumps that traveled across stage as his arms flung wildly; anguish, as he reached out to us with his body in an upside-down contorted arc, mouth agape, and, defiance in the finale, as he slowly sauntered upstage into the darkness.

Matthew Rushing’s, Uptown, was something altogether different. Almost more a musical theater piece than a ballet, it was most notable for its anthropological research. A character named Victor played by Amos J. Mechanic Jr., takes us on a journey through the Harlem Renaissance. He brings us to a “rent party”

(historically rent parties attempted to raise money by charging admission) that showcased some stellar swing dancing. We traveled into the minds of W.E.B. Dubois and Zora Neale Hurston; onto the Savoy to ogle Florence Mills, Josephine Baker, and Ethel Waters—all in sequins and feathers; through an audition for an all black musical on Broadway; and finally, to the Cotton Club. It is an exhausting tour.

Rushing’s ballet demonstrates the glory of the Harlem Renaissance and the debt current society owes to its great artists and innovators; yet, it glosses over the conflict and oppression that was also present at the time. A policeman coming to break up the “rent party” starts right on dancing with the rest of the crowd instead of, probably more realistically, bashing their heads.

Each work on the program reflected on Ailey’s inheritance: Rushing’s choreography was spiritual; Battle’s, provocative; Jamison’s, exhibitionistic; and Brown’s celebratory.

While no choreographer brought it all together, Battle’s In/Side was the most enjoyable.