The Dance Enthusiast in Philly: Impressions of Angel Corella and the Pennsylvania Ballet

Speed & Precision: Synesthesia on Steroids

Academy of Music, Broad and Locust St., Philadelphia, PA; October 22-25, 2015

CHROMA [Company Premiere] choreographed by Wayne McGregor

Set Design: John Pawson /Costumes: Moritz Junge

CONCERTO BAROCCO [Company Favorite] choreographed by George Balanchine

DGV [Company Premiere] choreographed by Christopher Wheeldon

Music: Michael Nyman / Set Design & Costumes: Jean-Marc Puissant

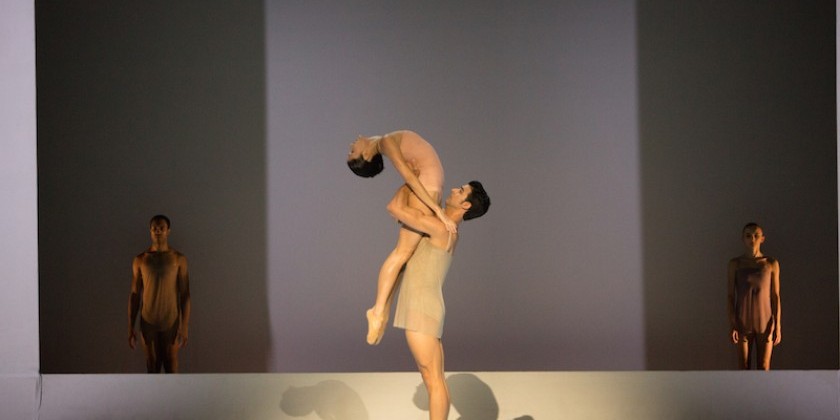

Pictured above: Pennsylvania Ballet Principal Dancer Arian Molina Soca and Soloist Mayara Pineiro in Wayne McGregor’s Chroma.

Dance is often a form of synesthesia, mixing one sense with another. In this first event of Angel Corella’s first full season as Artistic Director of the Pennsylvania Ballet, he has created an evening that is all about mixing movement with color, with music, and with story. Corella has put together what he calls his “dream season,” and this performance hints at the direction in which he wants to take the company. He has kept one company classic, the Balanchine-choreographed Concerto Barocco, but has sandwiched it between two more recent works — Chroma, choreographed by Wayne McGregor; and DGV: Danse à Grand Vitesse, choreographed by Christopher Wheeldon.

Although he wants to make changes, Corella is aware that he will have to move “step by step.” “This season will have a little something for everyone,” he says, and that includes those who love Balanchine, those who want full-length ballet or neo-classical ballet, as well as those who still want to see the company favorites.

The first dance, McGregor’s Chroma, to music by Joby Talbot along with his arrangements of music by the alternative rock duo The White Stripes, is filled with unexpected movement. McGregor, says Corella, “uses the dancer in strange ways. The body never stops moving.” As I watch the dancers, I think they move like insects with elbows, and edges, and curved backs. Yet they are elegant, precise, and relentless. They do things that don’t seem possible. A raised leg just keeps raising, pliés shift from side to side, dancers perform splits in the air while seeming to fly across the stage.

The stage is simplicity — white walls with an opening in the center back that turns color. The dancers in shades of beige and dusky rose take on the hues of the lighting. The music, by turns blaring and gentle, is surprisingly orchestral.

The precision of the program’s title is clear. Setting this ballet on classically trained dancers allows that preciseness to emerge. As a dancer, Corella says, “I always gave one hundred percent,” so that’s what he works on with the company — technique and precision.

“Dancers need to be a blank slate so that a choreographer can draw on them, as they want,” says Corella. He focuses on training dancers to be clean and clear without a particular technique already painted on them. “A good dancer is a good dancer,” he adds. Each technique has extremes, and going overboard can look strange. That’s why he gathers from all the techniques he has studied around the world.

Before the performance, Corella talks about the challenge of the shoes. Going from flat shoes to pointe shoes, those hard-tipped shoes that allow a ballerina to stand on her toes, requires warming up because the technique is so different. When the dancers have only fifteen minutes between dances to make that switch, it can be painful.

The second piece, Concerto Barocco, is described as a company favorite. The minute the dancers take the stage, you can hear the audience thinking “Ah, yes. This is ballet!” The music is Bach’s Concerto in D minor for Two Violins; the dancers, en pointe, represent the instruments we hear. We can settle in to enjoy something beautiful and familiar, not something that challenges our expectations. But challenge us is exactly what Corella wants to do. He hopes we will leave wanting to return because what we’ve seen is something unexpected and wonderful.

DGV:Danse à Grande Vitesse, set to music by Michael Nyman that was commissioned for the inauguration of the TGV high-speed train line in France, brings 24 dancers on stage as part of a journey that starts with an optical illusion making the dancers seem far away and small. The dance gains momentum as the train leaves, travels on, and then arrives. The dancers, dressed almost like athletes — swimmers, I think — and again en pointe, move in both classical and modern ways.

Changing the direction of a major ballet company is a bit like turning a huge truck. It takes time and has to be done carefully. Knowing that the company is based on Balanchine traditions, Corella wants nevertheless to expand its repertoire and its composition. While new as artistic director, Corella is not a total stranger to the company. His older sister, Carmen Corella, danced with the Pennsylvania Ballet from 1996-98 before joining American Ballet Theatre, where he was a principal dancer. “When I heard they were looking for an artistic director, I was first in line,” he says.

As a dancer with major companies around the world, Corella says, he was able to see and perform in a wide variety of ballets. Out of them, he has selected dances that he feels set the tone for where he wants to company to go. In the case of Chroma and DGV, he says, “I was incredibly lucky to have been around for their premieres in England. I’ve seen them live.”

Going forward, he has a lot of ideas. These include expanding the company, going on tour, investing in choreographers, and performing for more than one weekend at a time with great gaps in between. He particularly wants to “make dancers into movie stars, so that people care about them.” He wants audiences to say, “I’m going to see a particular dancer,” rather than, “I’m going to the ballet. I wonder who’s dancing.”

Corella is not new to the role of artistic director. In 2008, he established his own company, The Corella Ballet, which later moved to Barcelona and was renamed the Barcelona Ballet. Although considered one of the world’s best dancers, Corella says he gave his last performance in January, with his sister, for the King of Spain, who was visiting in Washington DC. For his own company in Spain, Corella was all things —artistic director, choreographer, dancer, even seamstress. He says it was just “not fair to the company, to the audience, to myself.” Now he wants to focus on the role of artistic director and bring his vision of the company into reality.