IMPRESSIONS: American Ballet Theatre in Helen Pickett's "Crime and Punishment"

Pickett is First Female Choreographer Commissioned to Create a Full-Length Ballet for ABT

Choreography, Co-direction and Treatment: Helen Pickett

Direction and Treatment: James Bonas

Music: Isobel Waller-Bridge

Sets and Costumes: Soutra Gilmour // Lighting: Jennifer Tipton // Video: Tal Yarden

Featured Dancers: Herman Cornejo, Catherine Hurlin, Claire Davison, Aran Bell, Skylar Brandt, Alexei Agoudine, Courtney Lavine, Jacob Clerico, Patrick Frenette, Jarod Curley, Joao Menegussi, Olivia Tweedy, Leah Baylin, Takumi Miyake, Kanon Kimura, Hannah Marshall

Venue: David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center

Dates: October 30 - November 3, 2024

Future Performances: Going to The Kennedy Center from February 12 - 16, 2025

Though it’s dark-toned, monotonously-paced, and not easily appreciated (it elicited only tepid applause at the performance I attended on Halloween night), there is much to be admired in American Ballet Theatre’s Crime and Punishment, a world-premiering two-act ballet based on the eponymous 1866 Dostoyevsky novel.

Foremost, is its consistently character-driven choreography. Created by Helen Pickett — the first female ever commissioned to make a full-length ballet for ABT — its every step is impelled by a clearly discernible thought, emotion, or personality trait pertinent to a particular character at a particular moment. A wide range of naturalistic hand gestures, and nuanced differences in attack, timing, and ballet vocabulary are employed to distinguish the work’s many characters. A detective performs precisely pointed, busy, little moves, while an angry snob dances with whacking arms, backward horse-like kicks, and strange bent-kneed jumps.

Dialogue-like, every move reads as a response to a previous physical statement from another dancer. Tender reaches, soft pats, caressing touches, and quick pull-aways of a hand speak volumes in a wonderfully minimalistic duet between an ardent lover and his reluctant partner. And Pickett keeps it all visually interesting by smart use of kinetic contrasts. When a determined suitor’s simple upturned palms scream, “I want you,” his unwilling prey delivers her resounding “no” with a grand jeté.

Despite its crystal-clear character relationships, keeping up with the ballet’s storyline requires some work. You must undertake a pre-show reading of the program’s long, dry, 22-scene plot synopsis, which may feel fruitless, as you won’t be able to remember it all anyway. But don’t worry. As you watch the ballet, captions are projected periodically to set the scene and provide reminders of what’s going on. If you read the synopsis, the captions prove more than sufficient to keep you on track with the narrative and are actually enjoyable to read, as the text is short, evocative, and, at times, poetic.

Crime and Punishment’s suspenseful plot tracks the impoverished student Raskolnikov, a nightmare-plagued murderer striving to evade capture for his crime, amid the social injustices and sorrows tormenting his cherished friends and family members. Unfortunately, there is a temporal sameness to how the plot unfolds on the ballet stage, as co-directed by Pickett and her collaborator, James Bonas. The staging lacks that stimulating mix of “fasts” and “slows” needed to sustain an audience’s attention throughout such a plot-heavy work. Also, not constructed of discrete dance pieces — with clear beginnings and ends, and rests in between -- the production presents a seamless stream of action which, while lending a graceful, cinematic flow to the storytelling, can make the viewing experience feel interminable. I’m reminded of how breezily one digests a book made up of lots of short chapters, while long passages of continuous writing prompt one to look for natural stopping places, breathing room, or a respite of some sort.

Another gender landmark, the ballet’s action-packed music by Isobel Waller-Bridge — the first female commissioned to compose a full-length score for ABT — almost single-handedly conveys the entire drama. Functioning like a film score, it generates a variegated spectrum of moods and energies that magnify the emotional impact of the narrative each step of the way. Most appealing is its stylistic diversity. I think I heard everything from folk-dance tunes, to jazz, romantic symphonic music, scratchy hard-on-the-ears string playing, propulsive Philip Glass-like passages, and melodies that sounded like 1960s television-show theme songs.

The ballet’s psychological-thriller atmosphere is ghoulishly established by Tal Yarden’s short videos, which appear intermittently to represent Raskolnikov’s re-playing of the crime in his dreams. And while Pickett’s unison ensemble choreography effectively conjures the foreboding energies of the urban environment, the story’s specific locales are ineffectually delineated by the reconfiguring of unadorned, rectangular wooden boxes on wheels, designed by Soutra Gilmour. Despite the re-arrangements, the setting looks the same for every scene.

Gilmour’s costumes, on the other hand, are delicious. They bring sparkling color and currency to the story’s bleak, industrial setting — which feels of another time and place, in its loose recalling of pre-Soviet Russia. Not only are the costumes telling, in their bright character-associated colors — shades of purple and lavender for the show-off who has more money than everyone else, and glowing yellow for the woman who offers hope — but, in a fun nod to today’s fashion, the main male characters sport tight pants that end well above the ankle, exposing colored socks that match the rest of their distinctively-hued attire.

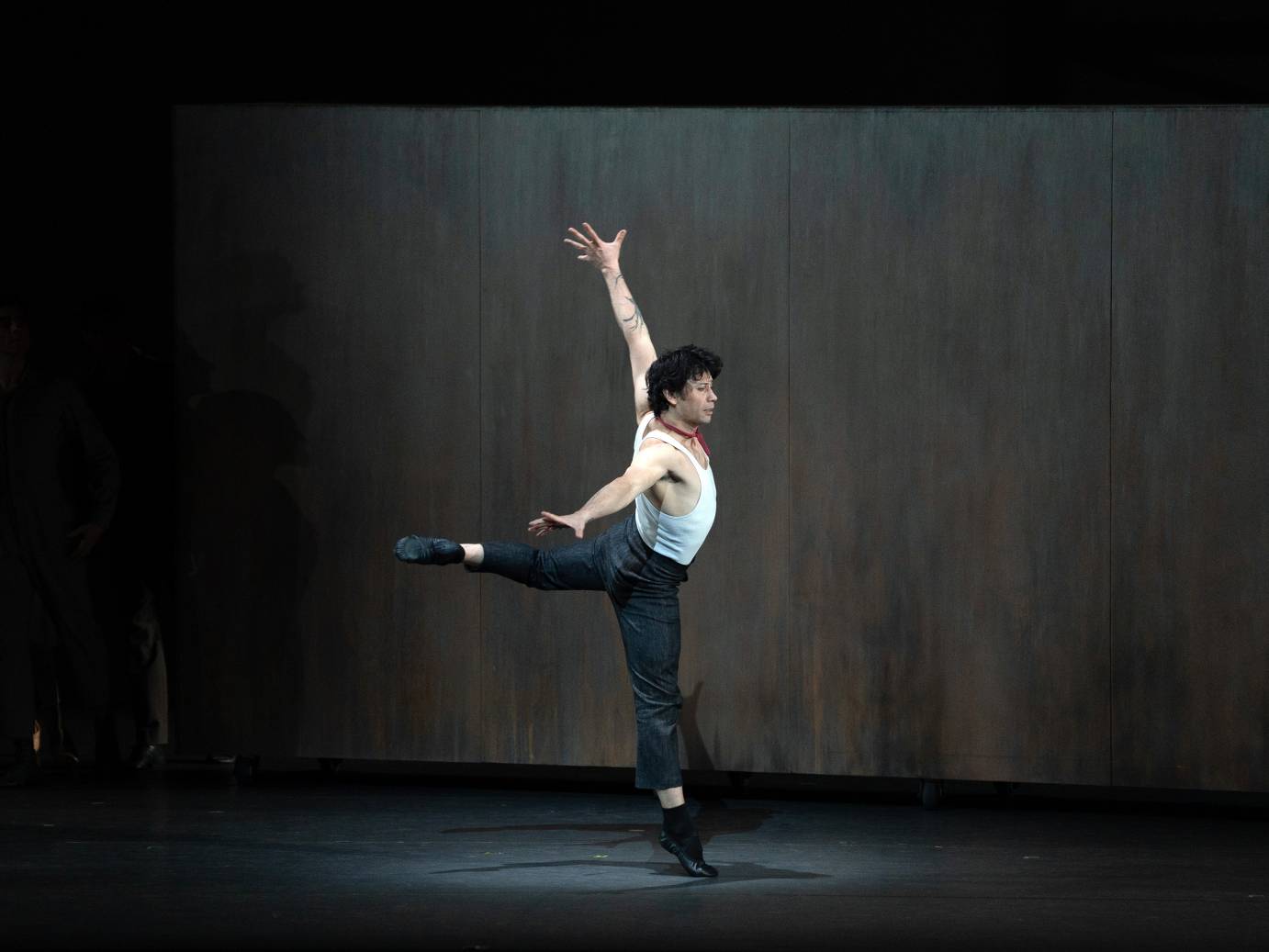

The production’s driving element, however, was Herman Cornejo’s expressive performance as Raskolnikov. Cornejo makes the character’s tortured inner landscape visible and palpable. A small dancer, he moves big all night — sweeping arm gestures, deep spinal curves, sudden altitudinous leaps, and spurts of dazzling turns. One can see large breaths of air traveling through and fueling the movements of his torso, and we feel the enormity of the emotions Raskolnikov struggles to contain. The ideal dancer to embody Pickett’s storytelling approach — her artful mix of everyday gestures and breathtaking ballet vocabulary — Cornejo is masterful at incorporating stunning technical tricks into phrases of pedestrian movement and making it all look of a piece.

Also keenly cast is Skylar Brandt, in the role of Sonya, an angel-like figure to whom Raskolnikov ultimately confesses his crime. Upon her father’s accidental death, Sonya performs a mournful solo. A gem of a dance, it’s one of the choreographic highpoints of the first act, and Brandt renders it with exquisite sensitivity.

Bravo, too, to Catherine Hurlin and Aran Bell — as Raskolnikov’s sister and his best friend — for their affecting performances of two duets: the first, beautifully understated, hinting at a love that has not yet blossomed; and the second, a gorgeous portrayal of passions finally permitted to live.