IMPRESSIONS: "AINADAMAR: A Fountain of Tears" at the Metropolitan Opera

Directed and Choreographed by Deborah Colker and Antonio Najarro

Composer: Osvaldo Golijov

Writer: David Henry Hwang

Projection designer: Tal Rosner

Lighting designer Paul Keogan

Sound designer: Mark Grey

Set and costume designer: Jon Bausor

Singers: Angel Blue, Gabriella Reyes, Elena Villalón, Daniela Mack, Alfredo Tejada

Flamenco Dance Soloists: Sonia Olla, Isaac Tovar

Almost a century after the Spanish poet and playwright Federico García Lorca was a lonely student at Columbia University, and twenty years after Ainadamar, an opera inspired by Lorca’s short life, made its premiere with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the work is being performed this season at the Metropolitan Opera House with sensual imagination.

The librettist, David Henry Hwang, describes Ainadamar, composed by Osvaldo Golijov, as an opera in three images. It weaves together the stories of Mariana Pineda, a 19th-century Spanish revolutionary, Lorca, and actress Margarita Xirgu, who knew Lorca as a young man.

Towards the end of Ainadamar, this fusion of an opera, a barefoot soprano, Angel Blue, blows on stage in her long, red dress singing “I am Freedom!” This stunning woman exudes joy and affirmation, yet this heartbreaking opera depicts the perils of asserting your will in a fascist state. Death was deemed the only retort to rebels like poet-playwright Federico García Lorca and Mariana Pineda, the latter martyred in 1831 for sewing a revolutionary flag and refusing to reveal the names of the rebels. Strikingly, a cross created with four tables and a mesmerizing light projection fades as the tables are turned. The cross morphs into some kind of gnarled being.

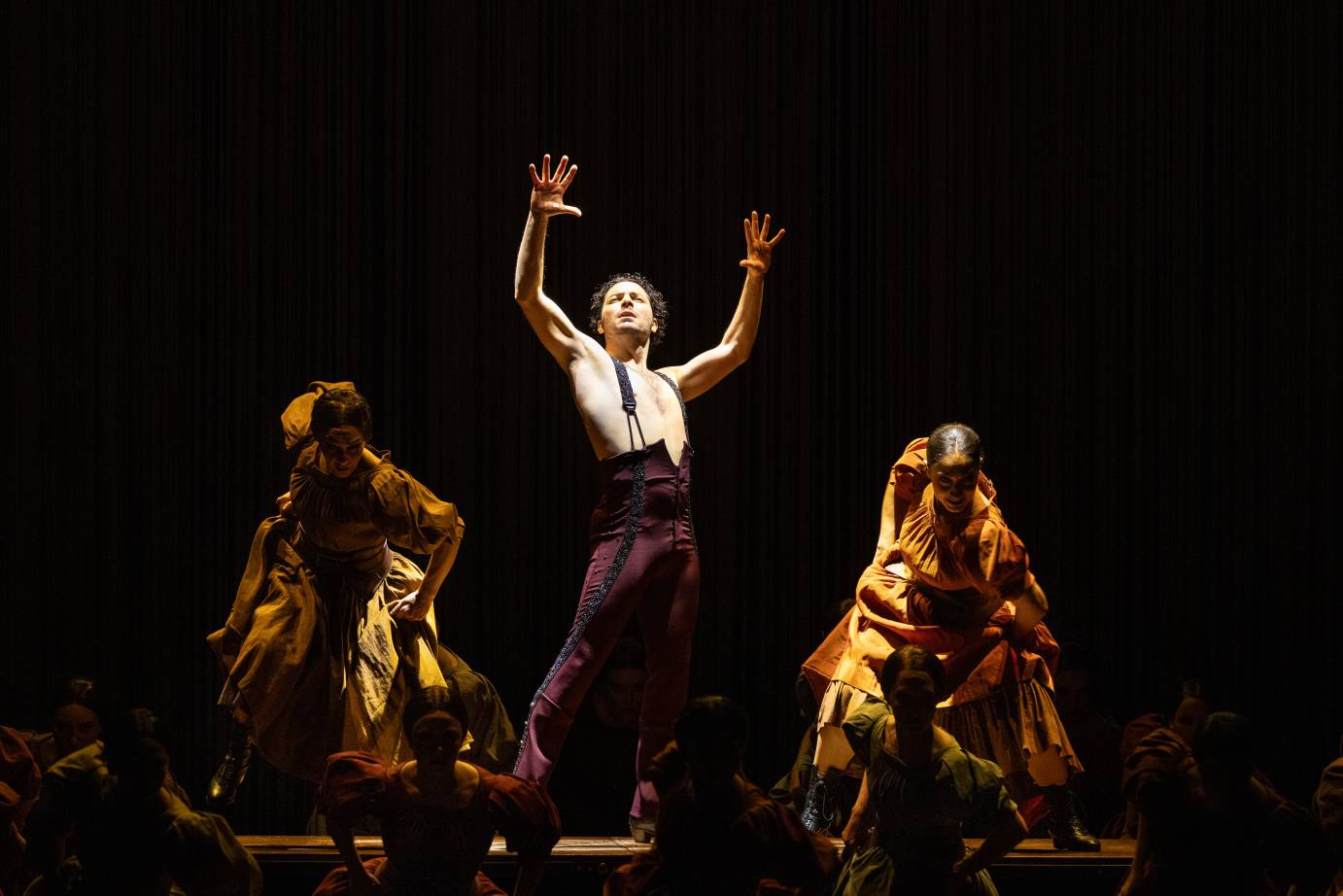

Tap Rosner has created a steady stream of evocative projections, beginning with a bull that seems to wrap around a bare-chested Isaac Tovar, who dances a glorious flamenco solo, on a raised platform. The clarity of his footwork and his iconic poses — the chest and chin lifted, his arms straight and piercing — is accentuated by percussive lighting. Tovar has a second solo midway through the opera, and Sonia Olla dances a fierce, deviant solo in a bata de cola. She performs on the four tables stretched into a runway that slowly turns.

Deborah Colker, the Brazilian director/choreographer, keeps the cast moving. The space seems to expand and contract as they billow out and in, and sometimes up. The cast, singers and dancers, seems to breathe as one. The ensemble dancers vent their frustration with full bodied thrusts of their arms in deep second positions to the audience, the sky, and or at the singers. Initially wearing earth-tone peasant dresses, the ensemble switches costumes to dance with fans that screech as they are flicked open. Four dancers stand on pedestals, perilously high, to swirl mantones at one point.

Much is made with fringe that sometimes encircles the raised platform, serving as a screen, or curtain, and creating an illusion of containment or privacy. Using only 4 long tables, sticks, and red fringe that descends from above, the set and costume designer Jon Bausor brilliantly collaborates with lighting designer Paul Keegan and the projection designer to create a visual feast.

The Argentinian composer Golijov continually surprises — using the sounds of horse hoofs, water dripping, and ominous spoken passages from 1930s fascists' radio broadcasts. Horns and harmonies sweeten the sonic landscape, with a rhythmic undercurrent that makes one want to sway. Despite the dire straits, music, poetry, and dance come to the rescue of our spirits.