Impressions of American Ballet Theatre in "Giselle"

June 16 – 21, 2014

Metropolitan Opera House, New York City

2014 NYC Spring Season through July 5

Performances watched:

Tuesday, June 17, 7:30pm & Wednesday, June 18, 2:00pm

With well over a hundred performances under my belt, the romantic ballet Giselle still continues to fascinate me. Night after night, as a young student at the Hamburg Ballet, I convinced the fireman, who was required by law to sit in a downstage wing, to give up his seat for me.

There I watched Count Albrecht court Giselle. With each petal she picked from the daisy he presented her, I would nod my head just as she did. Did he love her or not? When it looked like the petals predicted an unwanted outcome, Albrecht secretly pulled one extra petal to convince Giselle that his love was bright and sunny. What could go wrong after that?

But just as Giselle is a story of love, it is also one of deception, ghostly revenge, and redemption. Cue the Wilis. “Giselle, ou Les Wilis,” co-written in the 19th century by French dramatist Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-George and French poet, journalist, and art critic Theophile Gautier, is in part inspired by Heinrich Heine, a German poet. Heine explained that the Wilis are jilted brides, who died before their wedding and came out at night to dance men to death.

To this day many ballerinas dream of being Giselle. This is not only because Carlotta Grisi, the Italian ballerina who created the role for the ballet’s premiere in Paris in 1841, caused such a sensation that her salary quadrupled shortly thereafter. It is because Giselle was then, as it remains today, a seminal dramatic vehicle for a female artist. Where else can a dancer celebrate love, go mad, die of a broken heart, resurrect from death, and, last but not least, emerge as a forgiving otherworldly heroine? And, all of this happens in less than two hours in only two different costumes!

American Ballet Theatre’s production of the ballet with choreography by Coralli, Perrot, and Petipa, has been a company perennial. Costumes by Anna Anni and scenery by Gianni Quaranta set the stage for one of the ballet world's most beloved stories. The tale unfolds to the score of Adolphe Adam.

When the curtain opens, we find ourselves in a Rhineland village outside of the commoner Berthe’s house, where she lives with her daughter Giselle. The community is preparing for the annual grape harvest. When the business subsides, Hilarion, a gamekeeper, leaves several partridges ready to have their feathers plucked and a – presumably self-picked – spray of flowers in front of Giselle’s door. He must be in love. A castle in the distance reminds us that another social class exists. Count Albrecht, a member of that upper class soon to be wed to Bathilde, a woman of his station, visits the village to sow his wild oats. Upon arrival, he hands his cape to his squire, hides his sword in a shed, and, now disguised as the commoner, Loys, prepares to gallivant.

ABT sends a different cast of principals on the boards of the Metropolitan Opera stage for each performance during its week's run of this romantic masterpiece — a feat that should not be underestimated. On Tuesday night we saw the pairing of international superstars Polina Semionova and David Hallberg. Semionova, who trained at the Bolshoi before becoming Berlin State Ballet’s prima ballerina, recently joined ABT as a full-time principal dancer. Homegrown Hallberg climbed the ranks within the company from junior troupe member to danseur noble. He now divides his time between ABT and the Bolshoi, where he is a principal on both illustrious rosters.

From the moment Hallberg takes the stage as Count Albrecht he gives a detailed yet seemingly spontaneous performance. His Count is out to play, and disguised as Loys he falls for – you guessed it - the simple, charming Giselle.

There is much to enjoy in their love affair. When Semionova hops en pointe on one foot down a diagonal, she circles her other leg in front of her lusciously. An unaffected artist and a beautiful young woman, Semionova captures the appealing artlessness of Giselle in her solo passages.

No wonder Count Albrecht /Loys declares his passion. Does he toy with Giselle’s heart, or does he truly fall in love? Hallberg makes me believe the latter, but when confronted by his fiancée Bathilde, he realizes his wrongdoing. Giselle’s existence falls apart, and shocked by Albrecht’s duplicity, she goes mad and dies.

Always gorgeous to look at, Semionova gives a calculated and, at times, too demonstrative rendition of Giselle when she partners with Hallberg. I believe she would be more effective if she would let us witness her interaction with Loys rather than occasionally selling a moment by looking out at us. Here, some of her gestures lose intimacy. Surprisingly stiff in her mad scene, Semionova barely physicalizes her journey before she dies of a broken heart in Hallberg’s arms. As she indicates steps from previous happier, romantic segments of the ballet in her mad scene, I long for some sort of dramatic exaggeration to help me understand her character’s precarious state of mind.

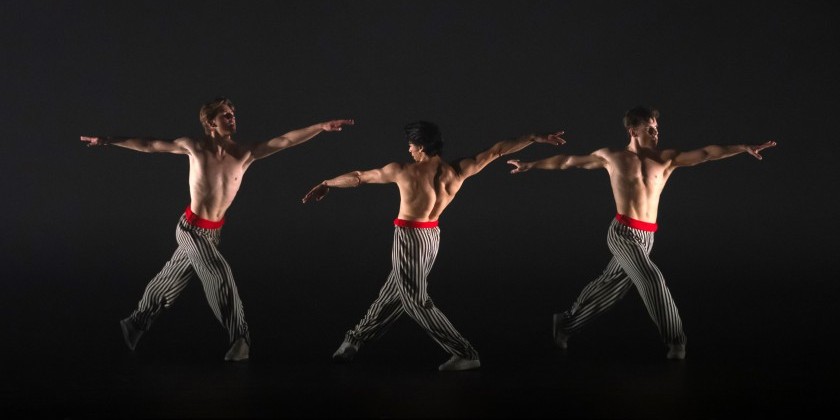

Wednesday’s matinee featured Isabella Boylston (at the time, a company soloist who has since been promoted to principal) and principal James Whiteside as the star-crossed lovers. Boylston shows technical acuity, showcasing security in her balances and light, unforced elasticity in her jumps. Her mad scene, though, is rather non-descript. James Whiteside is a handsome man and appears to know it. He points his foot all the way and displays it for a second before shifting his weight to take a step. Is it he or the character who is self-absorbed?

It’s worth noting that in the merry peasant pas de deux of Act I, Luciana Paris and Luis Ribagorda battle with the slow tempi of the orchestra and win. Ms. Paris hovers in her jumps and shows what a phenomenal athlete she is.

A forest graveyard at night is the scene for the second act. When Myrtha summons Giselle to rise from the grave to join the ferocious flock of Wilis, Semionova spins at lightning speed, regains her composure, and balances supernaturally. Boylston, too, seems at home in the spirit world.

Sadly, it is too late for the luckless Hilarion (Thomas Foerster and Patrick Ogle respectively). The Wilis are out for blood and dance him to death. Boylston’s Giselle, perhaps enchanted by Whiteside’s beautiful lines, saves him from Hilarion’s fate. The corps de ballet as Wilis does neither impress nor distract in either performance.

The revelation is Hallberg. His Albrecht pleads with Queen Myrtha to spare his life in a forceful diagonal of brises, beating his legs feverishly as his body leans to one side. Whiteside — as Hallberg did in prior years — performs a series of entrechat six (multiple upright beats of the leg), which unlike a charge for life look more like a circus trick. Brises are the better choice for the plot of the ballet.

Hallberg partners Semionova with love and assurance. Her beauty and the plastique of her line are a treat to look at, and more importantly, give her Albrecht the much-needed dance break that saves his life. Yet, I wonder if Semionova’s natural loveliness hinders her attempts to invest in deep emotion. Perhaps my inability to journey to the darker moments of the ballet is the result of being so charmed by her.

As Giselle retreats to her grave, Hallberg conveys remorse and kneels center stage humbled by her forgiveness. The dawn promises him a new day. While this is not a “traditional” happy ending, true love has won out over revenge, and I am left hopeful for Albrecht.