IMPRESSIONS: Dancing the 92nd Street Y, a 150th Anniversary Celebration

Dance to Belong: A History of Dance at 92NY

Co-curated by Ninotchka Bennahum and Jessica Friedman, with Jeanne Haffner of Thinc Design and Henning Rubsam as coordinating producer

Featuring:

Limón Dance Company:

Dancers: Natalie Clevenger, Joey Columbus, MJ Edwards, Mariah Gravelin, Johnson Guo, Kieran King, Deepa Liegel, Olivia Mozie, Eric Parra, Nicholas Ruscica, Jessica Sgambelluri, Savannah Spratt, Lauren Twomley

Choroegraphy: José Limón

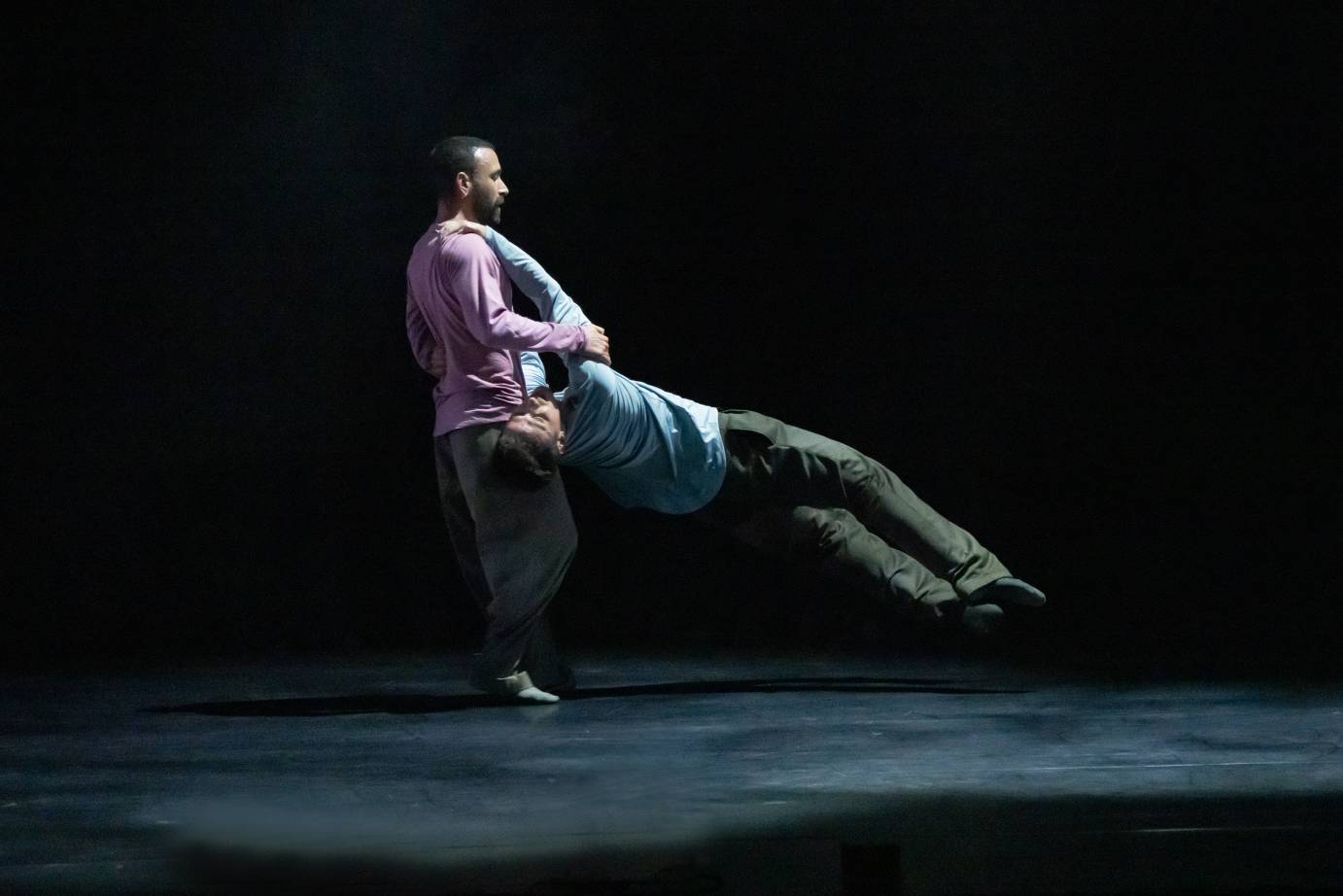

Omar Román de Jesús/Boca Tuya

Dancers: Omar Román de Jesús and Ian Spring

Choreography: Omar Román de Jesús

Martha Graham Dance Company

Dancers: So Young An, James Anthony, Ane Arrieta, Alessio Crognale-Roberts, Meagan King, Lloyd Knight, Jacob Larsen, Devin Loh, Marzia Memoli, Laurel Dalley Smith, Anne Souder, Richard Villaverde, Leslie Andrea Williams

Choreography: Martha Graham and Jamar Roberts

Ailey II

Dancers: Andrew Bryant, Patrick Gamble, Spencer Everett, Jaryd Farcon, Alfred L. Jordan II, Kiri Moore, Marie Oliver, Maya Finman-Parker, Kayla Mei-Wan Thomas, Maggy van den Heuvel

Choreography: Alvin Ailey

Hope Boykin

Dancers: Micaelina Carter, Baili Goer, Lauren Rothert, Bahiyah Sayyed, Amina Vargas, Martina Viadana, and Terri Ayanna Wright

Choreography: Hope Boykin

They could have just offered swimming lessons, but teaching kids not to drown did not satisfy the high-minded individuals who ran the 92nd Street YMHA. They had to get mixed up in modern dance. This was in the 1930s, and little did they know where it would lead. Promoted by Dr. William Kolodney and supported by rich benefactors, over the years, the institution, recently rebranded as 92NY, would become not merely a community center but a cultural hub with a special affinity for dance.

Now 92NY has reached a most respectable age — 150 years! — and while water-safety instruction remains a staple, the anniversary celebrations are drawing attention to 92NY’s contributions to dance both as an art form and as a vehicle for social justice. A gala performance in the Kaufmann Concert Hall on March 12 accompanied the opening of the exhibition “Dance to Belong: A History of Dance at 92NY,” which runs through October 31 in the Milton J. Weill Art Gallery.

%20Boykin%20Manifesting%20Legacy%20pc%20R%20Termine.jpg)

So many performers and teachers have passed through 92NY over the years that no exhibition could accommodate them all. The walls of the gallery are plastered with striking black-and-white photographs, interspersed with concert programs and moving images that bring the past to life; and the exhibition extends to a permanent installation on the 2nd floor. Co-curated by Ninotchka Bennahum and Jessica Friedman, and designed by Jeanne Hafner, with Henning Rubsam as coordinating producer, this wonderful show reflects a history in which physical culture, progressive politics, and intellectual aspirations all found an outlet in dance. Not all the artists represented are strictly modern. The Jewish ethnologist Hadassah is here, along with Indian virtuoso Indrani Rahman, and Native American dancer Tom Two Arrows; and a whole section is devoted to Black concert dance. Among 92NY’s proudest achievements is having hosted the premiere of Alvin Ailey’s Revelations in 1960. Recalling that the institution was founded to assist Jewish immigrants, and speaking of the moral values that underlie 92NY’s activities, CEO Seth Pinsky noted an “obligation to welcome and accept others.”

The gala performance showcased classic works by three of the most celebrated choreographers associated with 92NY’s dance center — José Limón, Martha Graham, and Ailey — pairing these pieces with dances by contemporary artists. How marvelous to revisit Limón’s There is a Time, along with excerpts from Graham’s Appalachian Spring and Ailey’s Blues Suite and The Lark Ascending. These works set a high standard for the new pieces that followed them, but perhaps Omar Román de Jesús’s fluent duet Like Those Playground Kids at Midnight will survive the inevitable winnowing.

There is a Time remains an artistic milestone. While Limón’s jumping off point was a verse from Ecclesiastes, it’s tempting to see more than a memory of folk-dancing in the chains of performers who hold hands, bending and twisting. Scientists had revealed the structure of DNA (the chain of life) three years before Limón choreographed his piece in 1956. Circles of various sizes are the central feature of There Is a Time, however, connecting this dance to the ouroboros, the mystic symbol of eternal return. Participating vicariously, we feel embraced in the communal round that opens the dance, and breathing with the dancers makes us conscious of our shared humanity.

Metaphors aside, Limón uses both circles and chains in a practical way to provide continuity, and to effect transitions between scenes in which soloists portray archetypal human experiences — birth and death, healing, planting, and making war. These are the themes, endlessly repeated, which define us as human beings. The challenge in performance is to make the archetypes personal, and the Limón Dance Company’s current cast succeeds marvelously. Lauren Twomley burns with intensity as she advances toward us clutching her extended fist like a weapon, in “A time to kill.” Limón gives this murderer a lingering moment to face her victim, revealing her hatred, before she strikes the fatal blow. In “A time to heal,” Deepa Liegel ministers tenderly to Kieran King, whose fluent movement quality shines even while supported. Mariah Gravelin performs with giddy energy in “A time to laugh… a time to dance.” Making a statement about inclusion, two men, M.J. Edwards and Eric Parra, dance “A time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing” the love duet which Limón made for himself and Pauline Koner. Savannah Spratt claws at herself, thrashes, and casts fearful shadows on the backdrop in “A time to hate… a time of war.”

De Jesús’ dynamic new work takes Limón as a starting point, echoing a pose in “A time to embrace…” where one dancer sits on the other’s knee. (Perhaps another point of contact would be the moment when Limón’s couple abruptly fall apart, holding fast by one hand.) Like Those Playground Kids reflects the discoveries of a later generation, however, particularly Steve Paxton’s exploration of contact improvisation. This athletic dance takes De Jesús and his partner, Ian Spring, on a wild ride. Flying, spinning, and tumbling around the stage, they find equilibrium only to teeter off balance into another unpredictable adventure. De Jesús and Spring are so involved in reacting to each other and grappling that they have no time for body sculpture. How ironic that the generation which championed pedestrian movement should also leave us with this legacy of mad virtuosity.

Gore Vidal once described our country as “the United States of Amnesia,” and so it is. Yet certain objects, and works of art, may linger to remind us where we have been. Martha Graham’s Appalachian Spring is a rich source of embodied memories, composed at a time of crisis (1944) when the nation required a sense of self. At the 92NY gala, the Martha Graham Dance Company performed sprightly excerpts from this ballet, contextualized by artistic director Janet Eilber’s narration. These selections emphasized joy largely omitting suggestions of fear and doubt. Yet much may still be read into the outstretched gesture of alarm with which the Bride reaches after the Husbandman, when he walks away from her; and even into the kiss which the Bride blows into the audience, bidding us farewell. Graham’s young, married couple recall the settlers who pushed past the middle border, leaving all they knew to struggle in a fertile, but untamed land. As the Bride and the Husbandman, Anne Souder and Jacob Larsen dance boldly, and give their parts dramatic weight. The Preacher (Alessio Crognale-Roberts) and his Followers add sly humor to this recollection of frontier life.

Jamar Roberts’ new We the People (also excerpted) projects similar feelings of hope and challenge, rendered in more abstract terms. Here denim costumes and a score by Rhiannon Giddens create a folksy atmosphere, but otherwise the choreography is on its own. Leslie Andrea Williams opens this dance of emphatic gestures by rearing back, and then bends down to sweep the floor. Perhaps she is clearing a path. Though moments of weakness assail her, Williams stamps and plunges forward. After dancing with two men, she brushes herself off and stalks away. While the ensemble may sway from side to side, and even sigh audibly, they share Williams’ attitude of defiance, drumming the floor with their feet. Everyone seems ready to fight.

The young dancers of Ailey II could have used another rehearsal, before tackling a suite of demanding Ailey Classics. That said, it is always exciting to watch the coiled and springing energy of the male ensemble in “Mean Ol’ Frisco,” from Blues Suite; and the virtuoso air-turns and tests of balance in Alvin Ailey’s Streams. On the dramatic front, Maya Finman-Palmer, Kayla Mei-Wan Thomas, and Maggy van den Heuvel bring taut desperation to "House of the Rising Sun,” from Blues Suite. Finman-Palmer rushes upstage as if seeking an exit, and reaches out in a poignant appeal; while van den Heuvel clutches at her throat and dashes herself to the floor. The most satisfying performance, however, comes from Kali Marie Oliver in The Lark Ascending. Tilting her shoulders to create this dance’s characteristic line, and moving swiftly and securely, Oliver takes possession of her role.

Hope Boykin's pièce d’occasion Manifesting Legacy features luscious Bahiyah Sayyed in a dance of entrances and exits, her comings and goings more interesting than the action centerstage. Sayyed plays den mother to a six-member ensemble, wafting and twirling past them or watching over her shoulder as individuals perform frisky solos. Sayyed doesn’t need to be center stage to command attention; and she doesn’t need to show off. She is glamour personified, and whether her soulful gestures are sinuous or broken, it’s clear who is in charge.