TEACHERS SPEAK: Legendary dancer STUART HODES recalls his students and what he learned from them

TEACH/LEARN written by Stuart Hodes 2008

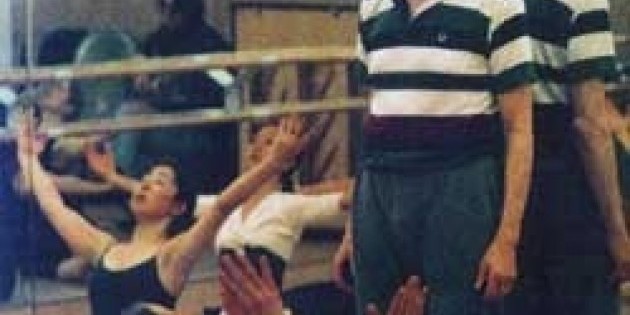

Stuart Hodes, 2005 Teaching Intermediate Graham Technique at the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance Photo ALFRED GESCHEIDT |

Former U.S. President, James Garfield, said, “The best university is Mark Hopkins on one end of a log and a student on the other.” The old pol may have been flattering his old teacher, who was present, but he captured a lasting truth. Good teaching is personal.

There are other ways to learn, especially now that there’s an Internet bursting with information. But not dance, or at any rate dance technique, which still demands direct transfer of knowledge from one from one body to another in a two-way process that changes both student and teacher.

Performing Arts High School, NYC, 1961. A vintage group included Janet Aaron. Bruce Becker, Louis Falco, Wesley Fata, Jane Kosminsky, Byork Lee, Michael Nestor, Michael Peters, and others who left their unique mark on dance. And on me. But one day they weren’t doing anything right. I was screaming my head off when Jane Kosminky danced by and said, “You can yell if you want, but we know you love us!”

Mid-October a year later, when Soviet missiles on Cuba were causing a flap, the whole class seemed to be dancing as if asleep on their feet. “What is the matter with everybody?” I yelled.

“We’ve been up all night.”

“What?”

“We thought the atom bomb would go off before morning and were on the telephone saying goodbye.”

We spent the rest of the class talking about why dance is important in a screwed-up world.

Good male dancers, potential company material, did not go unnoticed at the Martha Graham School. Before Paul Taylor became known for choreography, we knew him for his dancing. One exercise I often gave demanded a flexible spine. I happen not to have one, yet demonstrated as best I could. As I passed behind Paul, his flexible spine allowed him to bend way back, and as I passed, his eyes followed me. They seemed to say, “Eat your heart out!”

In Tokyo, 1955, the Martha Graham troupe was invited to a showing of student dances, and after it ended, Martha said that if any of them came to New York, they’d get scholarships. And they came, bringing talent and an intensity that amazed me and inspired Martha. They also brought a strict student/teacher divide, a line being blurred in colleges. Some teachers make the line between student and teacher bold, some soften it. I do the latter yet believe that to eliminate it altogether violates a trust. At NYU in the 1970s, an English teacher tried to eliminate it altogether. He insisted on being called by his first name, and asked students to create “their own mode of expression,” which did not need to include grammar, spelling, or punctuation. Brighter students complained that he wasn’t teaching them anything, so I was relieved when he said he needed to leave to “follow my guru.” He returned a year later, announcing that he’d achieved serenity and wanted to teach it to my students. When I demurred, his serenity shattered in a burst of four-letter words.

A dancer auditioned for NYU’s graduate program, and it was clear she was ready to work as an artist. I told her we’d be glad to have her, and asked why she wanted to come to NYU.

“I want to make dances and you have studio space.”

“For the tuition you’d pay, you can rent your own studio.”

She did, and invited me to one of her first showings. Her subject was simply space so she made the dance with people who worked with space every day. Architects. They bounded through their moves with the enthusiasm of border collies herding sheep, an early example of Johanna Boyce’s joyful, boisterous, and original contribution to dance.

When heading dance at NYU School of the Art (today Tisch), I insisted that all had to audition. The only exceptions were those in foreign countries who could send a video. I broke the video rule once, for Alan Tung, head of the Maurice Bejart School in Belgium, who said he had a 19-year-old who was “very creative.” Knowing Tung’s high standards, I took her sight unseen. She was small, gamin faced, bobbed hair, moved well, but without the spectacular physicality Bejart’s troupe was known for. Every afternoon I’d see her alone in a studio until one day she asked me to look at her solo to Steve Reich’s “Violin Phase.” She asked what I thought.

“It’s very good, but...”

“But?”

The music, insistently rhythmical, was almost uncountable and at the end simply stopped. Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker had continued past the stop to fade away. “You set up a powerful relationship with the music, but abandoned it at the end.”

She looked away. “I know it. Shit!” and shooed me out of the studio.

One week later, she’d nailed that impossible-to-count ending. The dance, “FASE,” now a duet, is still in repertory.

Anne Teresa stayed at NYU for one semester before returning to Belgium to establish her world-class troupe. I enjoyed not only her talent, but the notion that she was the closest I’d ever come to knowing what another genius, Martha Graham, could have been like at age 19.

Student dances are bright peaks, Joan Finkelstein’s "Depicting the Cranes in Their Nests," Ken Tosti’s "Diary of a Fly," Sean Curran’s dramatic adaption of Irish step dancing, Hilary Easton’s deft challenging constructions. So are students who did not dance, Bill Kleinsmith, who became a drummer, Missy Hoagland, a doctor, Peff Modelski, a writer.

Students without professional aspirations also left lasting impressions. I’d been at Manhattan Community College for two years when the students went on strike. I can’t recall their issues, but they surrounded the entire campus, turning back teachers, staff, and other students. As I approached, I thought, well, I’ll get the day off. But when they saw me a voice called, “He’s okay. He’s the dance teacher. Let him through!”