Choreographer Lionel Popkin Navigates A Cultural Legacy in “Ruth Doesn’t Live Here Anymore”

Abrons Art Center / 466 Grand Street

October 29-October 31 at 7:30 p.m., November 1 at 3 p.m.

For tickets, please click here

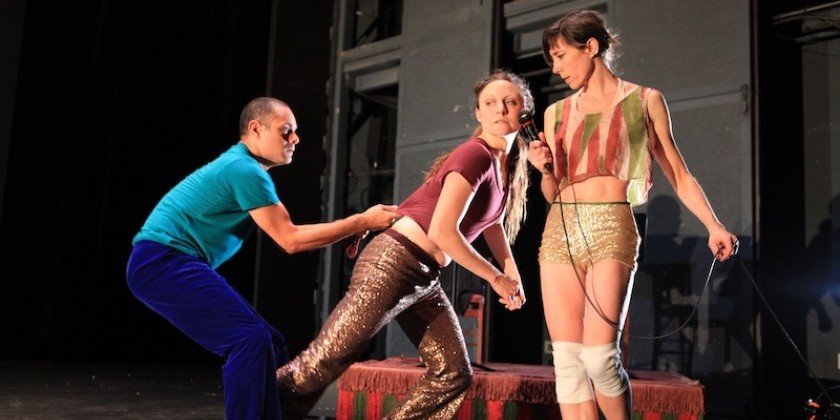

Concept and Choreography by Lionel Popkin / Performance by Emily Beattie, Carolyn Hall, and Lionel Popkin

Music by Guy Klucevsek / Music Performance by Guy Klucevsek and Mary Rowell

Legacies can be tricky things. The facts may stay the same, but as the gap widens between then and now, the interpretations of these facts often evolve.

Here’s a fact: Ruth St. Denis (1879-1968), along with her husband Ted Shawn, trained and inspired dance luminaries like Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, and, perhaps most notably, Martha Graham. Here’s another: Enthralled with Eastern societies, St. Denis created dances evoking exotic locales such as India, Egypt, and Japan that riveted American audiences. These two facts should assure her a prime position in the modern dance canon.

It’s not that straightforward, though. Contemporary ethos winces when confronted by the reality of St. Denis’ work: In what seems a blatant act of cultural appropriation, St. Denis diminishes rich and varied cultures to a handful of gestures and a pretty costume.

Her legacy is complicated to say the least. Stirred in part by St. Denis, choreographer Lionel Popkin investigates legacy and appropriation in the evening-length Ruth Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, which receives its New York City premiere at Abrons Art Center as part of Travelogues, curated by Laurie Uprichard.

Originally, the work wasn’t supposed to be about St. Denis. Popkin, whose mother is Indian, hankered to examine his own complex relationship with Orientalism. He’s incorporated his background into several pieces, even cooking a curry onstage in one. During Ruth Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, he dons his mother’s sari. The ethical implications of co-opting his Indian heritage to make art haunt him. He asks, “How much am I appropriating? Do I use my bloodline to make it more acceptable?”

Recognizing camaraderie between St. Denis and himself, Popkin spent a year and a half immersed in her records. “The piece deals with Ruth’s archives and how they translate over time,” he says. These documents reveal an artist with a strong vision, one based on curiosity — but not exactly reflectivity — about other cultures. “She dabbled right through,” he says, pointing out that after World War II, she moved to Los Angeles and redirected her interest to merging dance with divinity in the form of her Rhythmic Choir of Dancers.

Ruth Doesn’t Live Here Anymore engages the structure of St. Denis’ work but reimagines it with an expansive physicality. Popkin and two dancers (Emily Beattie and Carolyn Hall) follow St. Denis’ instructions— e.g., “three Oriental turns”— but embody them contemporarily by exploiting all the ways movement has flourished in the last hundred years.

This collision of past and present intrigues Popkin. In particular, air, through the presence of a lead blower in the piece, hints at how “the past acts as an unseen force on the present.” The music features a score by accordionist Guy Klucevsek, played live by the composer and violinist Mary Rowell. Popkin chose a composer who could mirror the spirit of the choreography: Take a historical legacy, in this case the accordion, and manipulate it afresh.

It’s easy to be, in Popkin’s words, “dismissive” of St. Denis. However, she wouldn’t have, nor could she have, identified her dance works as cultural appropriation. The Asian Exclusion Act, passed in 1924 and repealed in 1965, prohibited Asians from naturalization or land ownership, which curtailed immigration from the East. It’s unlikely St. Denis would have encountered circumstances that could have challenged her casual, profit-seeking appropriation where the costumes often took precedence over composing dances.

Popkin navigates his own cultural legacy with thoughtfulness, framing it as an advantage. “I don’t see things monochromatically,” he says. Making Ruth Doesn’t Live Here Anymore humbled him as he confronted the innumerable ways society has grown in the last one hundred years. In 2015, he asks, “What are we going to look back at and gasp?”