Colin Connor of Limón Dance Company: “The Season That Will Be”

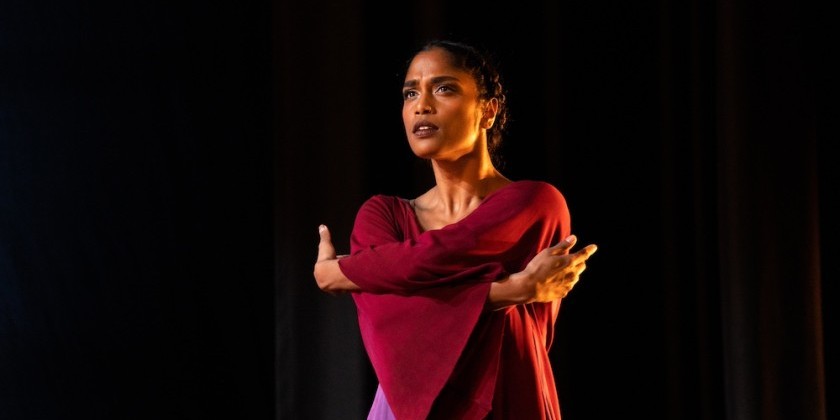

Limón Dance Company's "Virtual Seasons" @Limondance on Instagram

Though his plans for this season lie in tatters, Colin Connor, the outgoing artistic director of the Limón Dance Company, refuses to despair.

The nationwide theatrical shutdown prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic has forced this legacy modern dance troupe to cancel a series of eagerly anticipated engagements. Scheduled performances at New York’s Joyce Theater in March and April; at the American Dance Festival in Durham, NC, in June; and at the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, in the Berkshires, in July, all toppled like dominoes when the appearance of a virulent parasite unexpectedly gave the season a push.

Yet Connor will not speak of 2020 as “the season that wasn’t.” Instead he calls it “the season that will be,” and expresses hope that fall engagements at Aaron Davis Hall and at SUNY Purchase may yet occur.

Connor admits that the cancellations hurt badly, comparing the disappointment to what an injured dancer feels when obliged to take time off to heal. “If you get injured, you feel like your entire life is on hold,” he says. “And the entire society’s going through that right now.

“So much of what we do is how you are with other people, and how you are with space, and that is not going to be possible for us right now,” he adds. Though live performances are a non-starter for the time being, the Limón company has posted classes on-line, along with videos relating to the cancelled Joyce Theater engagement as part of what it calls a “virtual season.” (@Limondance on Instagram)

Connor is also happy to discuss the treats that the Limón company is keeping in reserve for audiences on the blessed day when we can emerge from quarantine and return to the theater.

At ADF, a premiere by choreographer Chafin Seymour was set to join the company’s repertoire of modern-dance classics, placing elements of hip-hop and release technique alongside works displaying Limón’s heroic images. The Durham engagement was also slated to feature veteran dancers Miki Orihara and Stephen Pier in Connor’s own work, The Weather in the Room, in which the group becomes a shifting emotional landscape that surrounds the couple with its energy. That engagement would also feature the revival of Limón’s Psalm, a timeless piece of Biblical inspiration dramatizing the tribulations of The Just Man in society.

At the Pillow, the repertory would have included a tribute to Limón’s mentor and friend, the late modern-dance pioneer Doris Humphrey. With a generosity unusual for his time, Limón had invited Humphrey to collaborate and direct his company when he founded it in 1946, making it a repertory ensemble from the outset. Talk about far-sighted! A film of Limón dancing solos from Humphrey’s Lament for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías (inspired by Lorca’s poem about a famous bull-fighter) would have prompted a series of interactive improvisations on the Pillow grounds. The troupe was also slated to perform Humphrey’s lyrical Air for the G String, to music by Bach.

Limón himself would have been the featured choreographer at the Joyce, where his company intended to offer Orfeo, a poetic meditation on death and loss that was among his last works; the plotless Mazurkas; and The Traitor, a powerful recounting of the Judas story that had political overtones when Limón choreographed it in 1954 at the height of Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s infamous anti-Communist witch-hunt. During that tragic period in American history, while McCarthy and his associates accused American leftists of disloyalty, those who denounced their friends and colleagues to Congressional committees to save their own skins displayed the most craven form of treachery.

Limón’s work was never overtly political, Connor says, explaining that viewers can contentedly regard The Traitor as a Bible story and nothing more. If they wish, however, they can go deeper, even connecting this more than 50-year-old dance with the tendency to political demonization that is rife in our own time. “We are in a time where the nature of loyalty and the nature of speaking truth are being challenged,” Connor avows.

Limón’s commitment to humanity and to social justice grew from his Mexican childhood and from his experiences as an immigrant to the United States. “He felt that everybody’s individual dignity was really important, and the desire to be in a community was really important,” Connor says. He adds that Limón was most concerned with “the psychic toll” of issues such as war and racism.

Few choreographers working today attempt the difficult task of crafting straightforward narratives, much less tackling Scripture or great works of literature, as Limón does in his masterpiece, The Moor’s Pavane, inspired by Shakespeare’s Othello. According to Connor, Limón did not regard Western Civilization as a burden, or feel inclined to disown it for its limitations. Instead, he regarded his own ability to engage with the great works of the past as liberating. “He was a voracious reader of the classics,” Connor says. “And I think he felt that as an individual artist when you stand shoulder-to-shoulder with these great artists of the world there are no boundaries; there are no barriers.”

The essence of Limón’s work, however, does not lie in the choreographer’s narrative interests, or in his skill in telling stories. According to Connor, what most defines Limón is his musicality: “this incredible rhythmic life that everything has,” Connor says.

“I think that is the way in for everybody, just the sheer beauty of his phrasing and musicality and how the space comes alive in time. That, for me, is a constant in every different kind of piece.”

Viewers who are new to Limón’s work should also note its strict economy of means and its lack of affectation, which Connor attributes to the clarity of intention given to every movement. The company not only suggests a group of “real people” dancing, but also telegraphs a sense of group solidarity. “We hire people who can create a community,” Connor says. “I don’t think it’s possible to show that community on stage unless it’s real.”

Connor, 65, who danced with the Limón company for eight years and has directed the troupe since 2016, will hand the reins to Dante Puleio in July; and it will be his successor’s job as artistic director to bring this historic troupe forward as it prepares to celebrate its 75th anniversary next year. Connor says he feels that during his tenure he has been successful in opening the company to new influences, and in preparing a new generation of dancers to carry on the company’s traditions.

“Just like everybody else we’re going through a really, very sad time,” Connor says, commenting on the current crisis. “But I am incredibly optimistic that we’re going to be able to come out of it. Limón is going to be able to come out of it. The dance community is coming out of it."

“We’ve just got to ride it out,” he says.