Jennifer Homans Was Wrong: Ballet Is Experiencing a Mini-Renaissance

Pictured above: Sara Mearns of New York City Ballet in George Balanchine's Serenade

It would’ve been funny if it weren’t so infuriating. In 2010, at the end of her meticulously researched cultural history of ballet, Apollo’s Angels, Jennifer Homans predicted that ballet was in an irreversible decline. She used her feelings (“I now feel sure that ballet is dying”) and gross generalizations (lumping all contemporary choreographers and dancers together) to project a dismal future for ballet.

In retrospect, the epilogue seems like a shrewd ploy to create buzz around a 600-page tome whose appeal may be limited. Homans’ predictions come across as quaint, the clucking from someone who was dismayed that the aughts sure didn’t look like the eighties (the decade at which Apollo’s Angels ended).

Like many rash and dire warnings, Homans’ has been discounted in the best way — by not coming true. Ballet is thriving, attracting new audiences and maintaining old ones because the world has changed since, was changing when, Homans wrote her augury. If she’d read the signs a little better, she might have envisioned what’s occurring on and off stages today. Ballet is enjoying a mini-renaissance, proving to be a surprisingly adroit language for the complex conversations we, as a society, are having about race, gender, values, and the blurring of barriers between private and public life.

Homans’ first mistake was to ignore the rapid advent of social media, which prizes short, shareable content. Ballet dancers are a natural fit for the medium with their sleek, tensile bodies that can be folded into an array of astonishing poses. Beauty and virtuosity stand as easy-to-appreciate qualities that spotlight the good taste of the poster and the person who likes that post. The best part of social media? Followers will sometimes share, thus garnering new eyes and potential new fans, via the best marketing tool around — word-of-mouth.

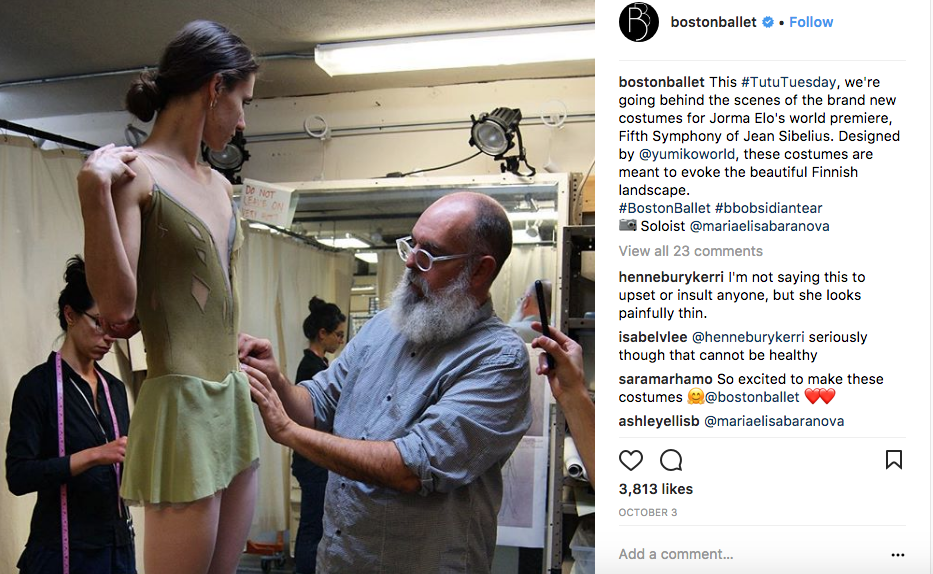

Instagram, in particular, has proven to be a boon for dancers and dance lovers. Launched in October 2010, it’s the incarnation of the old saw that a picture is worth a thousand words. Sara Mearns can lament her note from #alexeiratmansky to her almost 65,000 followers while Boston Ballet will show sneak peeks to their 153,000 followers of costumes for Jorma Elo’s premiere set to #sibelius. These behind-the-scenes glimpses soften the traditional boundary between stage and audience, fostering the feeling of intimacy, which can translate into revenue.

Ballet wields a potent weapon in is its superstars, who capture the public’s imagination through an alchemy of aptitude and mystique. While there’s never been a dearth of exceptional dancers, the 21st century hadn’t produced a Mikhail Baryshnikov or Margot Fonteyn, dancers who permeated the consciousness of the non-dance-going community.

Then, Misty Copeland happened — the first African-American woman who had a chance at becoming a principal dancer in the decades-long history of the world-renowned American Ballet Theatre. Her well-documented rise included a turn in a Prince video, an Under Armour campaign, and, most importantly, performing traditionally white ballerina roles such as Swanhilda (Coppélia) and Juliet (Romeo and Juliet). Attractive and articulate, Copeland handled the pressure — from injury to sustained critical attention, the latter of which has not always been polite — with grace, and in 2015, she achieved the rank of principal dancer to thunderous acclaim.

Copeland, though, points to a larger trend of dancers of color excelling at ballet. Although less fanfare greeted her promotion, the accomplishment was equally important: Stella Abrera became the first Filipina principal at ABT in 2015, joining Hee Seo and Herman Cornejo in a roster that’s starting to resemble the multiethnic world we live in.

Companies, while still more white than not, recognize that diversity and inclusion are core values of the 21st century. Ballet requires its practitioners to start young; hence, many schools like School of American Ballet and Ballet Tech have made it their mission to identify and to train children of color. In another decade or two, it seems possible that a Black man and a Black woman performing the leads in Swan Lake isn’t news; instead, it’s just the way the world is.

Part of Homans’ death knell stemmed from her assertion that the masters were all dead and gone. This claim was, at best, disingenuous, and, at worst, fallacious. Contemporary choreographers like Alexei Ratmansky, Christopher Wheeldon, and Alonzo King were curiously absent from Apollo’s Angels although all had amassed an acclaimed body of work by 2010. Arguably the most famous choreographer of the late 20th century/early 21st century, William Forsythe, was a literal footnote.

Homans’ larger point could be that no dance-maker has embodied the zeitgeist of the time. Art, though, abhors a vacuum, and in 2012, twenty-five-year-old Justin Peck premiered Year of the Rabbit to music by indie rocker Sufjan Stevens for New York City Ballet. The response was exultant. Millennials had found their voice.

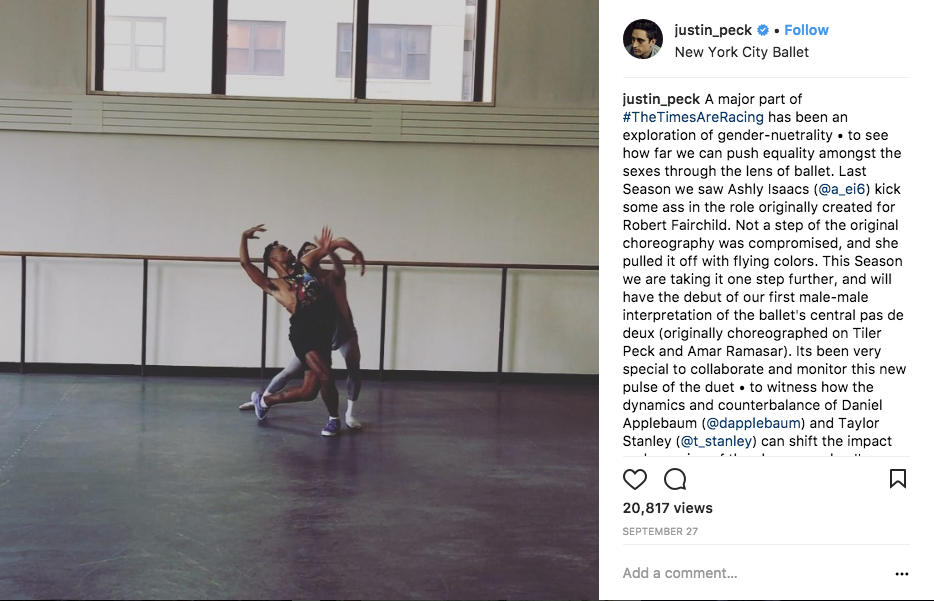

In short order, Peck became an in-demand choreographer for companies like San Francisco Ballet and Pacific Northwest Ballet that were eager to validate their commitment to keeping ballet fresh, relevant, must-see. His spirited, democratic romps of dancers coming and going in intricate configurations speak to this civically engaged, authentically realized generation. Peck’s tour-de-force, The Times Are Racing (2017), set to four songs from Dan Deacon’s vivacious America, features one of the first specifically conceived non-gendered duets — a showy tap-inspired number. It’s a knowing nod to a generation that’s not too psyched about conventional gender roles.

In five short years, Peck has secured the title of Resident Choreographer (he’s the second to hold it) at NYCB and enjoyed a full program devoted to his works. While only time will tell, maybe Peck will headline the next chapter in a future version of Apollo’s Angels.

In ballet, women have often commanded the stage, their leggy grace representing an ideal of heaven-reaching femininity that’s attractive to men and women alike. Yet they’ve been woefully underrepresented offstage, particularly in making dances — the true path to immortality in an art form that depends on eternal recreation.

Audiences remained unbothered by this disparity until, suddenly, they woke up. In 2015, when New York City Ballet commissioned four pieces from male choreographers, people wondered, where were the women? Peter Martins took the note and has programmed female choreographers consistently. In 2017, The Joyce Theater presented four female dance-makers on its five-program Ballet Festival. This series, which debuted in 2015, acts as a rebuttal in and of itself to Homans’ thesis: Venues aren’t in the business of showcasing work nobody wants to see.

More examples abound of ballet finding success and relevance in the 21st century. Companies continue to grow, adding second troupes and pushing trainee programs (the ethics of hiring dancers at low or no pay to pad out ranks is a topic for another article). The spirit of gesamtkunstwerk that characterizes ballet is alive and well with a video directed by David LaChapelle of Sergei Polunin dancing to Hozier’s “Take Me to the Church” achieving viral status.

And, in May 2017, Alexei Ratmansky both sparked debate about the depiction of women in ballet (Odessa) and introduced a new generation to ballet (Whipped Cream). If that’s not demonstrating an art form’s relevance to the world, then what is?

The Dance Enthusiast Shares OPINIONS and CALLS to ACTION from our editor-in-chief and Guests.

We Want You to Share Your Opinions on Dance You Experience With Us Here.

Share an #AudienceReview for a chance to win prizes.